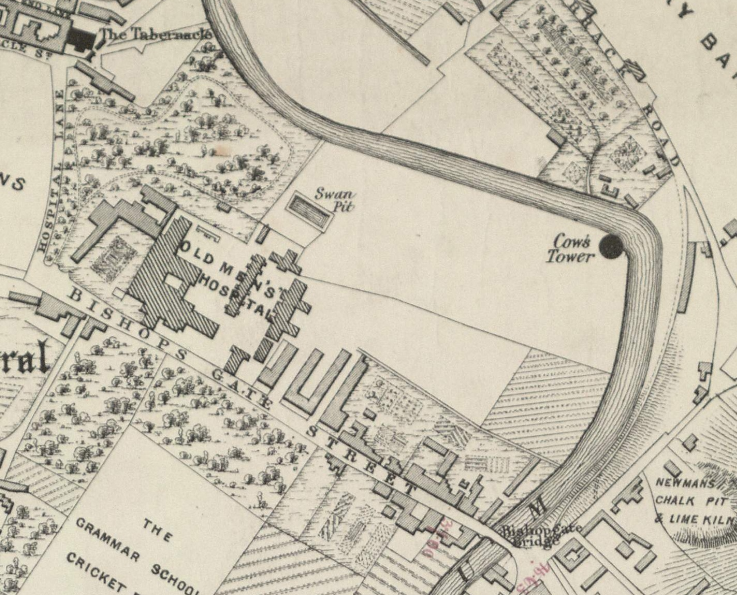

And a new little project that Jonathan and I are undertaking because this lockdown is clearly here for at least a few more weeks. It’s a bit niche (our project I mean, not the lockdown), I’ll accept that, but there we go. Effectively, it’s walking around Norwich, ancient parish by ancient parish and seeing what is there now compared to a map from the 1880s (the map above is from 1789, but the one from the 1880s is more detailed, which is why we used that). There’s a PDF of these boundaries to provide some extra background to this whole project.

So, starting our expedition, this is Bishopgate Bridge and three parish boundaries (St. Helen’s, St Mary in the Marsh and Thorpe) merge on this structure. Work on the bridge started in 1340 and a gate was added to protect the city soon afterwards, although that part of the structure was removed in 1790. Originally the bridge was owned and managed by the priory, but it became the responsibility of the city from 1393. The above photo looks down Bishopgate, the parish we were interested in today covers only the right hand side of this road.

The Red Lion pub, which closed in January 2020, but which is expected to open again under a new leaseholder when the current lockdown is over. This building is from the 1870s, but there was a previous pub on this site called the Green Dragon.

This is now the car park of the Red Lion, but it once had a number of houses on, some of which were near to the river.

This part of the river bank of the Wensum doesn’t appear to have been built on, although that metal structure to the right is likely the supporting part of the bank from the houses that once stood there.

The next stretch of the riverside path was once used as some form of allotments or vegetable gardens by the Great Hospital. It’s unlikely that there were ever any buildings here, it’s just a little higher than other sections of the riverbank, so might have been less liable to flood.

This area, which is partly flooded now, was used for grazing livestock and was probably useless for most other purposes.

And here is Cow Tower, and its name is from the cows which once grazed here. There have been some structural issues from the moist land that it sits on, but I think it’s done pretty well to have survived several centuries.

The tower was built between 1398 and 1399, used to defend against foreign invasion and local troublemakers. The latter caused the city some problems during Kett’s Rebellion in 1549, and the structure was damaged during that time.

The stairs that go up to the higher parts of the tower, which is all inaccessible now since the floors have collapsed. Much was demolished during the late eighteenth century, including many city walls and towers, but this survived. This was perhaps as it came under the care of the Great Hospital, who had no real need to demolish it. The building was patched up in the nineteenth century, but this was done by sloppy civil engineers and they caused large cracks to appear by their use of modern cement.

I had never noticed this art project by London Fieldworks before, designed to be occupied by birds and insects, it was installed here in 2011.

The next stretch of the River Wensum, again, this has never been built on and has likely only ever been used for grazing. All of this land was in the care of the Great Hospital, so nothing in this section got developed in the way that it might otherwise have done.

This is the entrance to the swan pit, which isn’t accessible to the general public at the moment. The whole situation here seems complex, and a member of the public added some comments as I was reading out what it said on Wikipedia (spoiler, the woman disagreed a bit with Wikipedia). I’m not a swan expert, but there appear to be two elements to all of this.

Cygnets (baby swans) were in Norwich owned by a number of different people, so they would be nicked on their beak to identify who owned which one. It seems that this meant that when they were older, and more grown up swans, the owner of the swan could be identified (swan upping is a tradition that still exists). Also, at the same time, the swan pit allowed swans to grow whilst being fed grain and not dirty muddy water, so they were forced into staying in a small area. When the swan was all grown up, it was killed and eaten (more information on this at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swan_pit). But, Joe Mason has much about this at https://joemasonspage.wordpress.com/2013/01/10/the-swan-pit/.

A hole has been punched through this wall more recently, but this was the end of the Great Hospital’s estate, which went down to the river.

The next section of land is now a car park (and it does seem that it could perhaps be better used for something else), but this was used in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as a timber yard. The wall on the right hand side (which contained a religious building that Jonathan and I didn’t realise was there – but more on this in another post as it’s outside the parish boundary) is now the courts complex.

The Adam and Eve pub is one of two licensed premises within the parish, although there were in the 1880s four pubs in St Helen’s. This might be the oldest pub in the city and would have been frequented by those who were building and maintaining Norwich Cathedral. It was certainly in existence in the 1240s, but is likely older. The current structure dates to the seventeenth century, although there is a Saxon well under one of the bars.

The new main entrance to the Great Hospital.

And this is the former entrance, which was on a blind corner and so not strategically useful in more modern times. The evidence of the old entrance drive isn’t hard to spot…….

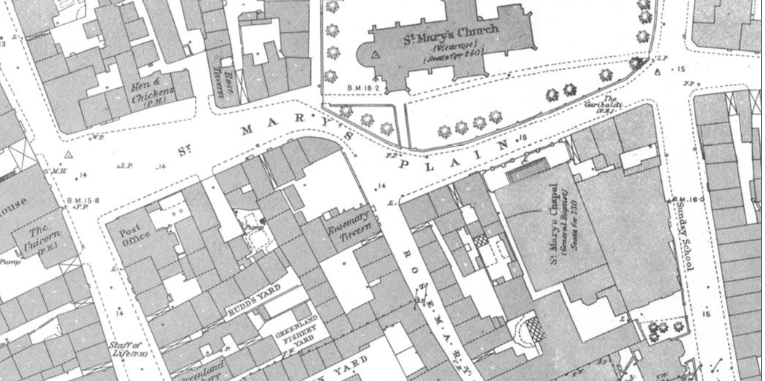

This is the main part of the Great Hospital, with the former vicarage on the left and St. Helen’s Church on the right. George Plunkett (is there anything this remarkable man didn’t do for Norwich’s history?) has drawn a map of the complex.

Going back a bit, this whole walk today was effectively on land owned by the Great Hospital, it was a powerful and wealthy institution. It had been founded in 1249 by Walter de Suffield and it helped retired priests and also local paupers. There’s a comprehensive history about the Great Hospital at http://www.thegreathospital.co.uk/, but one element is interesting and it’s the wait that the residents would have had at the Dissolution of the Monasteries to hear what would happen to them. They were lucky, not a great deal changed, just that the religious element of the institution became less important, but the charitable element remained.

St. Helen’s Church, a Grade I listed building of some considerable history, although this isn’t the first religious building on the site. When the Great Hospital was given the land and church in 1270, they decided to start planning a bigger structure, so the new and larger church was opened in the late fourteenth century and updated in the fifteenth century.

The main part of the nave is still used for worship, and is one of the few churches in Norwich that I haven’t been able to visit yet. The chancel end was turned into accommodation that was only closed in the 1970s, but the photos at the Norfolk Churches web-site better tell the story.

There’s a close-up of the text of that stone tablet at https://www.flickr.com/photos/norfolkodyssey/3788676616/.

And the final picture for this parish. As mentioned earlier, ignore everything on the left hand side of the road, that’s in a different parish….. The right-hand side has changed enormously, with two pubs having been swept away, the Marquis of Granby and the Rose and Crown.

So, this whole project is rather niche, although Jonathan and myself were rather engaged by this first attempt of ours. There’s an amazing amount of history which I’d managed to never notice before, although some has to be hunted for a little bit. Future parishes are larger, so will have more to challenge us…..