This figure was painted between 2014 and 2016 onto the end of this wall on Manor Road. I accept that it might not be Banksy, and indeed I accept that it’s nothing really like what he’s done, but I still like the imagery. I also like that no-one has painted over it during the last five years or graffitied anything else on the wall.

Category: UK

-

Chelmsford – United Brethren

The United Brethren pub is a short walk to the town centre, a little tucked away just off Moulsham Street. It’s not in the Good Beer Guide, but CAMRA noted that it was the sole pub in the Brighton based Pin-Up Pub Co estate (I’m not quite sure why their sole pub is nowhere near their brewery). The beer selection wasn’t quite as exciting as I might have hoped, it was limited to two real ales and no dark beers at all.

The service was though engaging and polite, so the environment was warm and welcoming, even though I was the only customer. I went for half a pint of the Captain Bob from the Mighty Oak Brewing Company, a reasonable session beer which is meant to have hints of gooseberry (I felt like I had returned to the Hop Beer Shop and the beer I had just had….) although I couldn’t detect them. It was well-kept and at the appropriate temperature, but nothing I’d write home about. Just write about here instead.

The decor seemed a bit muddled to me, but I’m not an interior designer and so struggle to comment much on that. There’s often music played here in the evening, hence why I went in the early afternoon. I looked back on Untappd to see if the beer selection was a bit more exotic before the health crisis, but it doesn’t seem to have been, although at least they had some stouts from Pin-Up. Anyway, all entirely comfortable and friendly, as well as being quite spacious (especially when you’re the only customer).

-

Chelmsford – Hop Beer Shop

This is another listing from the Good Beer Guide and is apparently, according to CAMRA, the first micro-pub which opened in Essex. I like micro-pubs as they usually have an informal and welcoming atmosphere, although these are challenging times for them as they’re often quite small in terms of their size. Hence the name…. Also today, the Government has confirmed that Essex is going into a different tier, which means that as from next week, this pub’s trade will be even more adversely affected.

The welcome was friendly and immediate, with the staff member finding me a suitable place to sit, which was about the last seat going. There were some interesting options for beers and ciders, with plenty of cans and bottles as well offering a wider choice. The environment in the pub was welcoming, even though all of the customers seemed to know each other. I suspect that someone new to the area would soon feel part of the crowd here.

I went for the Al Capone from Mighty Oak Brewing (which isn’t on the board as it had just become available) which is relatively local as it’s brewed in Maldon. The beer had a flavour of gooseberry, which isn’t necessarily something that sounds delicious, but it was an agreeable taste. The beer was well-kept, at the appropriate temperature and was something a little different.

The selection of cans and bottles that are available to take away. All told, I liked this pub, there was a laid-back environment, decent selection of beers and I can see why it’s in the Good Beer Guide.

-

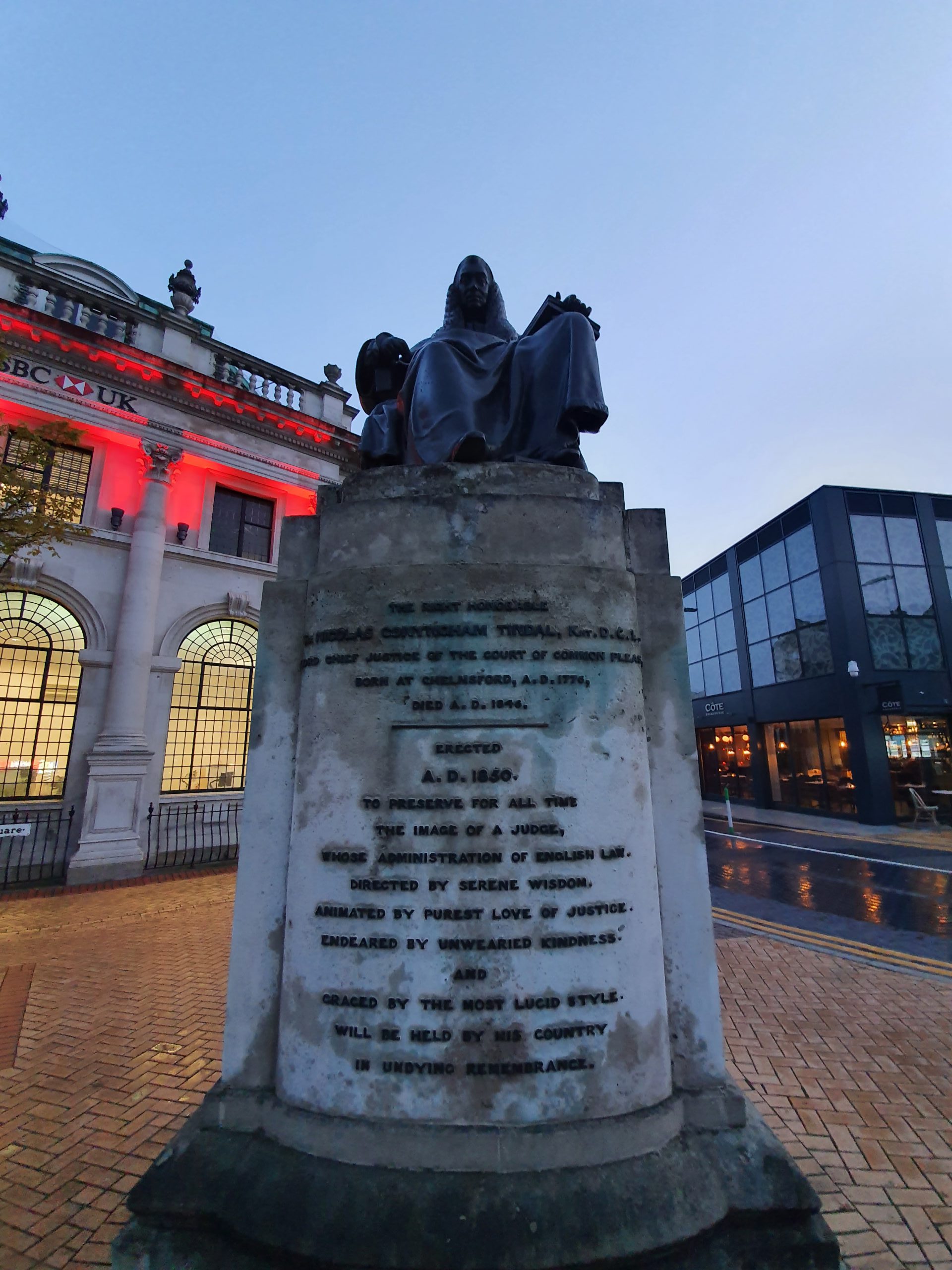

Chelmsford – Statue of Sir Nicholas Conyngham Tindal

This is the statue of Sir Nicholas Conyngham Tindal (1776-1846) and it was installed on the renamed Tindal Square in 1850. The bronze statue was designed by EH Bailey and sits on a sizeable stone pedestal.

Nicholas, if I can call him that, was born in Chelmsford and went on to become the Chief Justice of Common Pleas and a respected judge. He was also chosen to defend Caroline of Brunswick, the then Queen of England, at a trial in 1820 when she was accused of adultery. The King didn’t want her around, but the people loved her, so Caroline wanted to assert her role as Queen. The defence was successful, but the whole situation was a little ridiculous, even at King George IV’s Coronation in 1821, Caroline wanted to attend and he barred her at the door of Westminster Abbey. Sounds quite an exciting drama.

-

Chelmsford – The Ship Pub

I’m not particularly keen on Greene King pubs, as I may have mentioned a few times before, as the excitement of choosing between Ruddles or Greene King IPA can be too much for me to bear. But, the Ship in Chelmsford is in the Good Beer Guide, so I felt there must be something special about it.

The interior is themed as a ship, which is handy given the pub name, and I like the decor as it’s quirky but not ridiculous. The pub was also busy when I visited in the early evening, indeed, busier than the other two Good Beer Guide pubs that I had just visited. Based on that popularity, it’s clear that the pub is doing more than just a few things right, with a really relaxed ambience.

More ship stuff. In normal times I would have taken better photos and meandered around the pub looking at old things (decor I mean, not customers), but now isn’t the time to do that. The service was friendly, prompt welcome at the door, table service and a knowledgeable staff member. There were three beers from Greene King and one from Bishop Nick brewery, the Respect. This is a red ale which was acceptable if not riveting (note the word play there given ships….), which was the best choice I could see given that there were no darker options. It was all OK, but I’m not sure I’d want to recommend anyone comes here who likes craft beer or dark beer, but there are nearby alternatives for that.

One thing puzzled me (again), which is that the pub’s web-site says that its beers are supplied Ridley’s Brewery. Ridley’s Brewery was a major site in Hartford End, which Greene King bought out and shut down, like lots of things they do. The Bishop Nick beer I had is from a new brewery established by a relative of the Ridley family and they supply to a large number of pubs in Essex.

I’m not particularly bothered about what my beer is served in as long as it’s clean, although it’s not entirely usual to serve real ale in a Guinness glass. But, anyway, this pub is clearly providing a valuable community service (that sounds like some reoffender project) and the reviews are generally positive, particularly for the food which is served. Based on that heritage and welcome, I can see why the Ship is listed in the Good Beer Guide….

-

Chelmsford – Turtle Bay

Turtle Bay were once my favourite UK chain, serving decent Caribbean food which had a bit of spice to it. I felt that they went downhill a bit across the country last year and I’ve mostly ignored them since. However, their app gave me a free meal earlier in the year in Norwich which was rather lovely, and they’ve now sent another on-line voucher. I certainly won’t complain.

The interior is bright and decorative, with the staff member who served me being pro-active and engaging.

Some considerable thought has gone into the design of the toilets.

This is Turtle Bay’s own milk stout, which I think is made by Hunter’s Brewery. Tasted OK, sweet and creamy, although not a great richness of flavour. But, it’s nice to see restaurants making an effort like this and I’m not sure why the Caribbean has a history of stouts, perhaps it’s down to Guinness Foreign Extra Stout.

The meal which Turtle Bay kindly gave to me, which is the half a jerk chicken with spiced fries. The chicken was very tender and fell straight off the bone, with the portion seeming quite generous to me. Fries were decent, crispy on the exterior and fluffy on the interior, but I still have no idea what bloody use that watermelon is to the meal. But, perhaps it’s authentic, I don’t know. The chicken was a bit blackened in places, but I like that, I’m not a fan of soggy chicken skin, I like it firm and a bit burnt.

I’m not sure that Turtle Bay is as good as it once was, but it’s certainly better than it was at its worst. The service here was above standard and they delivered a clean and comfortable environment. The Grace Jerk BBQ Sauce in the bottle which is on the table is still beautiful, I suspect I went through the majority of the bottle. Anyway, since this meal cost me the grand sum of just under £5 for the beer, I certainly can’t complain and I note that the recent reviews for the restaurant are pretty positive. So, hopefully the future for Turtle Bay is bright in these challenging times.

-

Chelmsford – Public Footpath Signs in Field

This is an image (© IWM D 4282) from the wonderful Imperial War Museum photo collection, taken in the Chelmsford suburb of Springfield in August 1941.

It shows a whole load of public footpath signs which have been taken from locations around Essex to ensure that any landing German has no clue where to go. The signs were placed here in a bid to deter aircraft from landing in the area, making for an interesting looking field.

-

Chelmsford – Railway Tavern

Located near to the railway station and the Ale House is this pub which looks quite small from the front, but is suitably long and sizeable when looked at from the side. It’s listed in the Good Beer Guide and so I felt that it deserved a quick visit.

There was a friendly welcome from the barman and there was a traditional feel to the interior, a proper pub. There’s a railway theme, which isn’t a surprise, and there were plenty of locals drinking (I took the photo during a brief quiet spell) but it wasn’t cliquey.

Some of the railway decor.

The barman apologised that there were no stouts or porters, he explained that they didn’t have the trade for them at the moment. Most of the customers seemed to be ordering lagers, so I can understand his difficulty here. He did though have a mild, which I think is a decent compromise, which was the Black Prince from Wantsum Brewery. The beer was better than I had anticipated, smooth and with a pleasant aftertaste. Wantsum are a brewery from Kent and their beers are named after historical events or people, which is a quite marvellous idea.

I liked this pub, all a little understated perhaps, but it was what a pub needed to be, which was welcoming and homely. The beer selection isn’t exceptional at the moment, but these are troubled times and I liked that the barman explained that there’s normally more. This seems to be a worthwhile addition to the Good Beer Guide in my view, a little treat for those who need a drink before getting their train.

-

Chelmsford – Ale House

Back to Good Beer Guide pubs, the Ale House is located near to the railway station and has some excellent reviews. I got a bit confused as to whether I was meant to wait outside or go in, but on trying the door it was locked, so I worked out that I was meant to wait outside. Until a staff member opened the other half of the door, so I suspect I looked like an idiot standing outside. The staff member didn’t say anything though, I like when they pretend not to notice stupidity….

The beer list which is also helpfully on Untappd, so I had seen what the pub had to offer before arriving. A nicely balanced selection with plenty of different beer and cider types.

And there were cans and bottles for those who preferred, with some very tempting options there.

A wall display.

The bar is in railway arches and if someone had somehow missed that, they’d soon know from the trains thundering by overhead. I liked it, it all added character.

This is the De La Creme from Mad Squirrel Brewery which didn’t quite have the richness of taste that I had anticipated, although it was a perfectly good milk stout. I think that the De La Nut from the same brewery, which I haven’t tried, might have a little more depth to it.

The service here was personable, attentive and welcoming, a friendly atmosphere. The staff were carefully following all the required rules and it was a comfortable and clean environment. Some very tempting options and if I didn’t have other pubs to explore then I’d have tried a few more beers here. My favourite pub in Norwich is the Artichoke and this is pretty similar, with many of the can options being those I’ve seen in the Artichoke.

-

Chelmsford – Tank on a Roundabout

I’m not sure how many cities have tanks made out of willow on their roundabouts, but it’s one of the things that Chelmsford has done to mark the 75th anniversary of VE-Day. There are two tanks on the roundabout, one is a British Sherman Tank and the other is a German Panzer Tank, both of which were designed by the local artist Deb Hart. Apparently it takes 26 bundles of willow to make a tank and they certainly add some character to the roundabout.