Continuing with my theme of events that happened 150 years ago today, the Norfolk Chronicle reported in late February 1871 that Thomas Edgar had been charged and tried for the theft of a scarf from the Coach and Horses pub on Red Lion Street whilst the owner was playing skittles. I’d never realised that pub existed and it suggests an answer to a question I had of whether skittles was commonly played in Norwich in the past.

Anyway, back to the details of the court case, although this was just the first hearing. Thomas Edgar, who lived at Crook’s Place (that unfortunate fact isn’t lost on me…..), visited the Coach and Horses pub and I suspect he didn’t plan any nefarious activity when he arrived. However, Frederick Leech (named as William Frederick Leach in another newspaper) who lived at Oxford Street, located off Unthank Road, had arrived with his expensive cashmere scarf. I’ve got a picture in my mind of what I imagine he was like, but others can draw their own mental image here….. Leech was enjoying a game of skittles and had placed his scarf neatly on his hat and put that on a table. After a while of enjoying his game of skittles (the paper didn’t mention the score) he realised that his scarf had gone missing and he then saw Edgar rushing out of the pub looking suspicious. Leech left the pub and tried to follow Edgar, but lost him and so he contacted the police. The police rushed out and found Edgar and the missing scarf at Crook’s Place, which sounds some rather excellent detective work. Edgar’s defence was that he was drunk, which doesn’t seem unreasonable as far as excuses go.

For some more information about this, I had to jump forwards a month to late March 1871 when the full trial took place. More details came out, including that Edgar had offered to look after the hat and scarf, which doesn’t seem to be a very subtle way of pinching something. The detective work from the police was explained, a police officer and a man called Piggin had followed Edgar to his home and this wasn’t some brilliant piece of guesswork. Edgar’s defence was accepted, which was that he was so drunk he didn’t know what he was doing. These were ferocious times in terms of sentencing though, and when Edgar was found guilty, he was sent to prison with hard labour for six months. The additional reporting also noted that Leech (or Leach) was an ironmonger and Thomas Edgar was aged 21.

Rolling back a little here, the pub itself, the Coach and Horses. This was located at 3 Red Lion Street and it’s still there today, although it’s now a Bella Italia having ceased being a public house in around 1984. The building was constructed by the brewery at the beginning of the twentieth century, on the site of an older building and the one where Edgar pinched the scarf from. And we also know that the pub had a skittle alley judging from the events of that night, and it also had a three dimensional bas relief panel by notable local artist John Moray-Smith. That is now sadly lost, although there’s one of his works remaining at the nearby Woolpack pub.

Back to Thomas Edgar though. He was born in 1849, the son of Matthias Edgar and Mary Ann Edgar and at the 1861 census he had four older brothers and sisters. Mary Ann was from Devon and the two oldest children had been born in Plymouth, but Thomas was born in Norwich. The family at this stage lived at 44 King Street (probably not where most people would think this was, but more on this in a moment) and Matthias worked as a brush maker.

The 1871 census isn’t entirely helpful about where he lived, since he was in the city gaol, which was at that time at the end of Earlham Road (or St. Giles’s Street at the time, before a bloody great road was built at Grapes Hill orphaning the end of it), which is now the site of the Roman Catholic Cathedral.

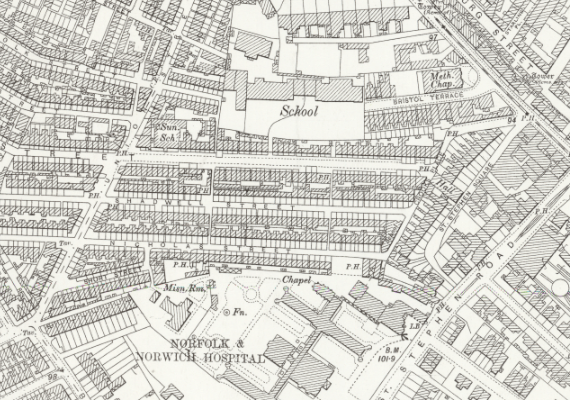

We do know from the newspaper that he had been living at Crook’s Yard and this is where things got a little confusing for me, as I’ve now discovered that there were two King Streets in Norwich at that time. Not the Upper King Street and King Street that we have today, which are still really the same road. Some bloody idiot had built a King Street and a Queen Street (ignoring the fact that these street names already existed) near to where the Norfolk & Norwich Hospital was located in the city centre. This clearly caused complete confusion at the time as records from the time are all over the place, but wiser heads prevailed and King Street was renamed Shadwell Street and Queen Street was renamed Nicholas Street. In the above map, Crook’s Yard (or Crook’s Place) is the road leading off from the right. It’s possible that this name confusion meant that Thomas was still living with his parents at this time on King Street.

At the 1881 census, Thomas was living with his mother at 44 King Street and he was working as a waiter. By 1901, Thomas was now married and living (alone, for reasons unknown if he was married) at 86 Shadwell Street and was working as a fruit-seller. Thomas died in the city in 1910, at the age of 61, and there is no mention of his death in the local press. At a guess, 44 King Street and 86 Shadwell Street were probably the same house, but either way, they would have been demolished after the Second World War.

But, the element of all this that I quite like is the thought of the atmosphere in the Coach and Horses in the city 150 years ago. I’m not sure that skittles is played much anywhere, not least because it’s quite space consuming, but there’s an equivalence with bar billiards. And I can imagine a similar set of circumstances playing out, someone leaving their expensive cashmere scarf out (and I can think of a couple of friends who would turn up at the pub with something like that….) and finding that it was stolen. Thomas Edgar doesn’t seem to have been a particularly bad person, he certainly didn’t have a long life of crime after this incident. And I’ve tried to work out the route that he would have taken from the pub back to his house (I bet he went down St. Stephen’s, walking by where there is a Greggs today), perhaps testament to the reality that I need to get out more.