I already have a better explanation (well, longer explanation anyway) for this plan. In essence, whilst lockdown is on, I need to find ways of walking nearby to Norwich in quiet areas for my LDWA 100 training. So, I’m using GeoGuessr to pick out five random locations within a certain area which I’ve defined and then walking to them, to see what kind of story I can uncover.

The five random locations, all fairly close to the city centre, so this ended up being a walk of just under seven miles. Nathan was helpfully understanding when I turned up late as I bumped into (not literally) someone I knew.

It’s a little difficult to find anything new in the centre of Norwich given how much I’ve been traipsing around it, so the more mundane may become more predominant. But, perhaps there’s something just as magical about these old stones under the road surface than a building that was constructed at the same time. The paving here on Barrack Street is likely the best part of a century old and it was part of a long roadway down towards the River Wensum, although it’s mostly gone now.

This was the first location, Whitefriars Bridge, which I’ve written about before…..

This, until recently, was the Del Ballroom on Waggon and Horses Lane which was used until 2013 as a dance studio. Norwich City Council decided that as there was a dance studio nearby, this interesting and quirky building could be torn down, despite some local objections from nearby property owners. I suppose it’s not a hugely historic building, as it was only built in the 1930s, but it added some character to the local area. The seven new properties they’re cramming into the site don’t have car parking provided and no right to a permit, so it’s all quite environmental in terms of not adding cars to the roads of Norwich. Anyway, I digress……

Our second location and this photo was taken from just outside the rather lovely Strangers’ Hall Museum. The Strangers were Dutch Protestants who were invited to live in Norwich by the city authorities and so many came that they eventually comprised a third of the city’s population. They did much to boost the textile trade in Norwich and also helped the local economic situation, with relatively little evidence of any animosity between locals and incomers. There’s a strong legacy in the city today of Dutch style buildings and it was the migrants that brought over canaries, which is the city’s football symbol today.

This is the former site of St Benedict’s Gate, also known as Bennet Gate and Westwyk Gate, which was demolished at the end of the eighteenth century. A little bit of this gate survived until the Second World War air raids destroyed it, as can be seen in this George Plunkett photo. Today, the route of the city wall and the outline of the city gate is marked out in brick paving which is always a marvellous idea.

The line of the wall looking up towards Grapes Hill.

Our third location, the former Britannia pub.

The pub was opened in 1975 and closed again in 2000, now being used for housing. It’s really not the most attractive of buildings, but I’m sure that the city council thought that this was marvellous when they approved it in the early 1970s. The pub was built to replace the Sandringham Arms, an interesting Victorian building which had been a licensed premises since the 1860s.

The Rose Valley Tavern, or whatever name they’ve fiddled it about to now, which has been a licensed premises since the mid-nineteenth century.

And Nathan had put chips on the agenda for the evening’s walk, which was a most useful idea. I’ve never been here before, so another first, this is Lee’s Fish Bar on Chester Street.

Full marks for presenting chips (and a battered sausage) like this, they were much easier to eat and this is proper innovation as far as I’m concerned. Also, I discovered that they had given me scraps with the chips, and I very much like them. I was in rather a good mood with Nathan for some time after this little meal. The chips were quite salty, but I liked that, indeed, they catered very well for me here.

Fourth location, which is Leopold Road. I’m not going to comment on the history of this road as I didn’t pay any attention to it at the time, so that would be a bit fake….

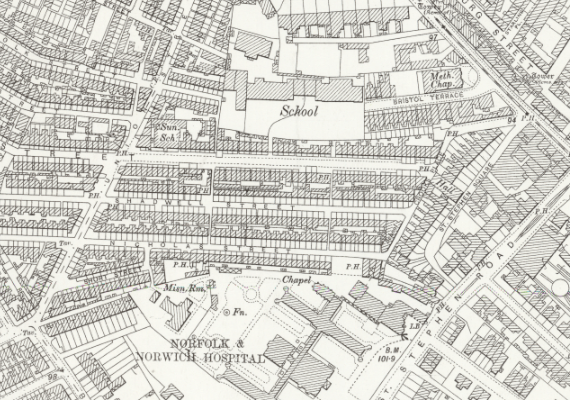

This is the railway crossing which goes under Hall Road, although the line isn’t there any more, it led into what was Norwich Victoria Station. This was a complete mistake IMO to remove, as the lines connected in, so the city could have trains running into the centre of Norwich, opposite the bus station. An integrated public transport policy. Although, it’s important to note that passenger services ended here over 100 years ago, in 1916, and the station was used primarily for goods transportation after that.

Nathan was doing the navigation for the evening and he excelled himself (I hope he doesn’t read this, he’ll quote that for ages) in the choice of route towards our fifth location. This is the former city wall at Carrow Hill and George Plunkett took a photo here in 1934 when it was covered in rather more ivy.

At this point it was dark and we were navigating by torch light down this hill Nathan had chosen, but it took us under Wilderness Tower. I promise that I won’t enter this photo for any photography competitions.

There are some reasonable views of the city from up here.

And then by Black Tower, although I accept that there’s not a great deal of detail visible in the photo. I’ll walk by here again in the day to take some more photos I think.

And we dropped down to near Norwich City Football Club for our fifth location and I’m unsure why GeoGuessr keeps giving random locations around here. I have more photos of the side of Morrison’s than is healthy for someone in their late 30s / early 40s…..

Anyway, this was an easy way to add a few more miles of walking in, as it’s really not long until the LDWA 100….. The weather was mild, which was fortunate, as it’s annoying to get drizzle when trying to get chips on the go.