This is the rather beautiful St. Andrew’s Church in Lamas, notable perhaps because of its off-centre chancel. And below is a plan of the church rebuild in 1887, with the kinked chancel particularly noticeable. The design of this plan was by Herbert J Green (1851-1918) and although the chancel was rebuilt, it was constructed on top of the previous structure.

Author: admin

-

Panxworth – All Saints Church (1846 plan)

I haven’t seen this plan before, it’s of the new nave for Panxworth Church which was designed by James Watson in 1846. It’s clear to see just how the Victorians got so many of these designs produced, it’s a generic plan which was rolled out. In the case of Panxworth, the building of the new section of the church was almost speculative as there wasn’t a congregation to support it and the nave has since been demolished.

-

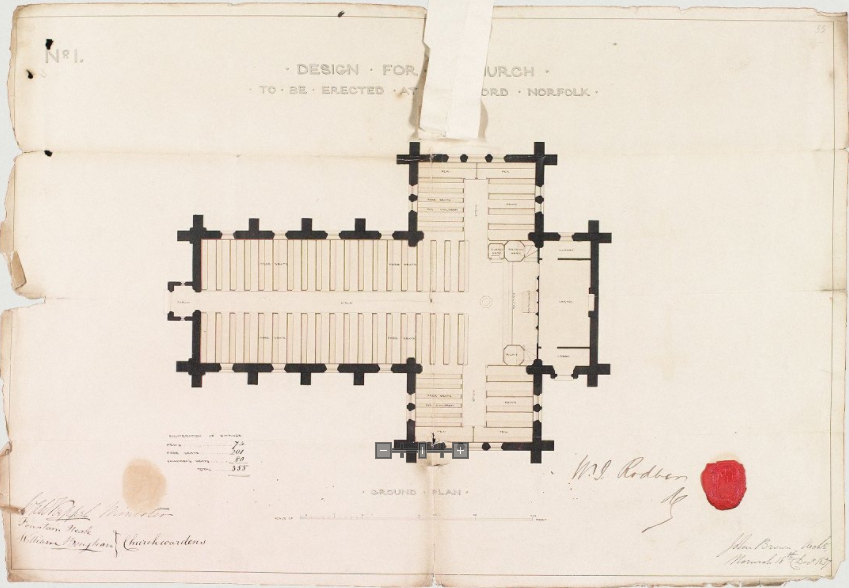

Hainford – All Saints’ Church (the new one) – plan of building

This is the plan that John Brown (1805-1876) drew for the building of the new All Saints’ Church in Hainford, dated 1837 and so just before construction of the new church began. There were 74 seats on the pews, 201 free seats and 80 seats for children (these were located in the transept).

-

Hoxne – Name Origin

The village of Hoxne in Suffolk that Liam and I walked through on our 27-mile walk…… It’s a slightly strange name (Hoxne I mean, not Liam) and this is what The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Placenames says…..

Hoxne, Suffolk. Hoxne in 950, Hoxa in Domesday Book, Hoxe in 1121, Hoxna in 1232. The place is on a spur of land between the Waveney and one of its tributaries. The name is probably OE hohsinu, meaning heel-sinew which, to judge by the later hockshin, hough, was probably used also in the sense of ‘hough’. The place was named from the similarity of the spur of land to the hough of a horse.

That’s one of the more complex reasonings I’ve seen and it’s also of note that the place-name today is the same as in 950 (that reference is from the Cartularium Saxonicum).

And the village sign, which was only introduced here in 2019. It makes reference in its design to the Hoxne Hoard that was found nearby and also to King Edmund (the King of East Anglia from 855 until his death in 869), who might have been martyred nearby. It would have been a clearer photo if we’d have got round the walk a little quicker I must admit.

-

Spixworth – Name Origin

The above photo was taken from the graveyard of the rather lovely St. Peter’s Church in Spixworth. And this is what The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Placenames writes about the village’s name:

Spixworth, Norfolk. Spikesuurda in Domesday Book, Spicasurda in 1163 and Spicheswrtha in the twelfth century. Spic’s Word, the first element being a nickname, perhaps derived from spic ‘bacon’, or simply ‘bacon farm’.

Firstly, that’s an interesting place to live, somewhere called bacon farm. Rolling back a bit though, the worth is from the Anglo-Saxon ‘weorthig’, meaning a protected place or some form of enclosed land. So, the meaning is either an enclosure belonging to a person called Spic, or, as suggested, a bacon farm (and the German word for bacon is still ‘Speck’). I think I prefer the bacon farm theory.

-

Spixworth – St. Peter’s Church

One exciting element about old buildings is that they often just don’t make sense (OK, they do to experts, but I mean make sense to me). There have been centuries of bits being added on, changed, removed, refurbished and faffed about with, ending up with a church that looks like this. But, this Grade I listed church is very much unique, and is more beautiful because of that.

It took me a while to fully understand this building, but in the above photo, the vestry is on the left, then the nave with the larger window, then the south aisle and then the tower. The chancel is behind the nave and the tower once stood separate from the main part of the church. It is though likely that the tower was once connected to an older church, from the early Norman period, that was entirely removed.

The dating is more complex, but the base of the tower was likely first, then the nave and chancel are fourteenth century, the south aisle is fifteenth century, the rebuilt tower is from the same period (although the different brickwork is from when the top of the tower fell down in the early nineteenth century) and the vestry is much newer (some records say late nineteenth century and some early twentieth, but I doubt it makes much difference to anything….). Or, that’s my best understanding of what is a complex building way beyond my architectural knowledge….

This is the chancel, at the rear of the church.

And, from the other side of the building, that’s the tower at the rear, then the south aisle in the middle and the side of the chancel on the right. The Victorians didn’t maul this building about too much, indeed the church was restored during this period since the roof was falling down and this wasn’t seen as ideal….

An old pew being repurposed as an outdoors seat.

Little stones, which I suspect would have been moved about by two boys that I know….

The church has this rather lovely woodland trail, with burials alongside part of it.

This is an internal note from the 1960s now released by the Church of England, although I’m not sure that the denizens of Spixworth would be delighted at the description of their “silly little tower”.

-

Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue – Day 227

The Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue was first published at the end of the eighteenth century, and given that the current health crisis is giving too much time to read books, I thought I’d pick a daily word from it until I got bored….

Norway Neckcloth

Grose makes a lot of references to words and phrases relating to punishment, whether it’s the gallows or the pillories. This one relates to the latter, defined as “the pillory, usually made of Norway fir” and the phrase remained used until the mid-nineteenth century, pretty much when the pillory was banned in England and Wales in 1837.

There had been discussion in Parliament about whether the pillory should be abolished for some decades before the ban was enacted, with the problem that some found themselves rewarded by the public with flowers and refreshments, whereas in other cases the criminal was killed by mobs during the punishment, so the law failed in both ways.

-

Hainford – Hainford War Memorial

The village of Hainford’s war memorial is located in front of All Saints Church, commemorating the 25 local men who died during the First World War. A number of local men also died during the Second World War, but their names haven’t been added to this memorial.

The calvary cross with canopy was unveiled in the early 1920s, although this is the first memorial that I haven’t been able to find the exact date for. One of the sides had the names restored recently as they had become hard to read, although the base of the memorial does perhaps still need a little further attention.

-

Hainford – All Saints Church (the old one) – William Garrod + Amy Garrod

This is the tomb of William Garrod and his wife Amy Garrod, once located under the nave of All Saints Church in Hainford. The church was partly demolished during the period around 1840, meaning that this tomb suddenly found itself out in the graveyard.

I don’t much about this husband and wife, other than William died on 24 April 1681 and Amy died on 20 February 1681. Slightly amazingly, the burial records from this period have survived and are in the care of Norfolk Record Office, although there’s no information I can see on them which adds to the story. So, although I can find out nothing exciting about the Garrod family from the seventeenth century, it’s an interesting reminder of the church that was once here.

-

Hainford – All Saints Church (the old one) – John Thomas Coleman

This grave is located to the side of the old All Saints Church in Hainford, next to the fenced off tower. It commemorates the life of John Thomas Coleman, who served in the 36th Battalion of the Australian Infantry. Normally, I’d spend ages faffing around with censuses and newspaper reports to work out what has happened for this Australian man to be buried here.

However, a lady called Cathy Sedgwick has already gone into some considerable detail with what she has found, with her information about John located at https://ww1austburialsuk.weebly.com/hainford.html. In short, John had been born and raised in the area, with his parents Charles and Maria running the general shop in Hainford. John went to Australia when he was 18 years old and remained there until he was called up to fight in the First World War. He never fought on the front line, as he sadly contracted pneumonia en route to the UK and he died on 9 January 1917, at the age of 26.

The National Archives of Australia have John’s service records freely available here.