We were sailing home back to Norwich on the last bus from Fakenham and were just a few miles outside of the city in Lenwade when this happened. And I’ll start this story by saying that the drama adds something to the day and I wasn’t personally troubled, but I do get annoyed when public transport companies treat customers in such an off-hand way. Apologies for the mostly self-serving overly long moaning, but I’m quite edgy about getting any of their later services.

To cut a long story short, the road was closed for quite substantial road works to Lenwade bridge. I was hoping that the construction work was to build a new Greggs, but it seems that they’re just repairing the current structure. Not as exciting, but clearly necessary. There was a debate for a few minutes between the engineers and the bus driver, which was polite, but fruitless. The engineers were not letting the bus through and so our double decker bus was a bit stuck.

The driver contacted someone, I assume at First, and the passengers downstairs (we were upstairs, but could hear) were told that the Norfolk County Council authorised works had started early and that the signage was inadequate. I don’t need to further investigate this, I checked the county council web-site, and the road works are authorised. It is regrettable that any representative of First should be saying this, as what the engineers were saying was correct, that First bus should not have been there. There were quite some allegations made about those engineers and I hope that First get in touch with Norfolk County Council to withdraw them. But that’s all a bit serious and not really relevant to this already seemingly never-ending story.

Anyway, these things happen and I’m very placid as delays on public transport are hardly new to me. Someone hadn’t realised that there were road works this weekend and that the bus shouldn’t have been there. There was also confusion from many other road users, so it’s clear also that the road signage here was perhaps really not ideal from the County Council and their representatives. However, bus companies should probably have a better understanding of this, but, mistakes happen.

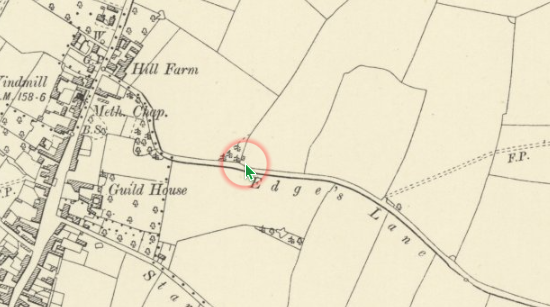

The view from the front of the bus of the drama, which is about as much excitement as I get until we can travel further afield.

We sat upstairs for thirty minutes (the situation was moderately entertaining at that point) and could hear what was going on downstairs. I was surprised when I heard the bus driver say that the passengers upstairs were just sitting there as I wasn’t sure what he expected us to do. We were rather waiting for instructions from him, although perhaps he wanted us to be more pro-active somehow.

Anyway, there was another bus driver behind, on what I assume was the First bus service back from Fakenham to Norwich which didn’t have passengers, as it had terminated service back in Fakenham. There was some discussion between First, their two drivers and an off-duty driver. They got one passenger to go in a private car driven by an off-duty driver, which didn’t seem a usual way of dealing with things, but that’s perhaps not entirely relevant here.

We were then told that the only option for us was to get back on the bus, and the bus would go from the outskirts of Norwich back to Fakenham, through to Swaffham and then to Norwich. That was a bit of a ridiculous journey (which the driver admitted was “very long”) and clearly a bad call. I asked what happened if passengers needed the toilet and why was there no contribution towards a taxi. The bus driver told me that passengers could urinate at the back of a house now, in partial view of other properties, and she said there were no other options as legally there was no way a bus could stop anywhere else. She told me to contact First if I didn’t want to take that option.

It’s not entirely clear how I was expected to contact First in the highly limited amount of time offered to me and I’m not entirely sure it’s really the customer’s role to do that. So, in this exciting story (I accept I need to get out more), we have a passenger being driven back in an off-duty driver’s car, we’ve got passengers told to urinate in a semi-public place and a total disregard for what the five passengers actually wanted. No-one was asked if we needed water, if we were on a deadline and the taxi option clearly wasn’t happening. I accept the water option is a bit of a side point, but any welfare related questions would have been useful just to ascertain the situation. Disability awareness is important and was ignored here, although the details aren’t really relevant here with regards to that.

As can be seen in the photos, it got dark during this meander around Norfolk. To keep the passengers awake, the driver sounded his horn on average once per minute. I didn’t understand what that was about. The bus managed a decent speed during this tour of Norfolk, but it still really wasn’t an ideal situation. I did vaguely hope that the driver would pop into the McDonald’s in Swaffham, but that didn’t happen. I quite fancied some Chicken McNuggets, but recognised that wasn’t really a likely scenario. This is a far cry from when I was in the United States and a bus driver needed to get out to use the toilet and he came back with snacks for me for the inconvenience (no pun intended), but that’s a different story.

And back in Norwich, two hours late…..

This was a far from ideal situation (as I may have mentioned) and it was entirely caused by First’s management, this wasn’t the fault of the drivers. Travelling what seems nearly constantly on public transport, the situation on the rail network is brilliant. Passengers would be given water, provided with a taxi, toilet facilities arranged and checks usually made to ensure there were no vulnerable, disabled or confused individuals. It’s also very easy to contact rail companies, or is in my experience, and although things have gone a bit askew, they’re nearly always on top of problems.

These solutions were all available to First, the taxi journey would have been fifteen minutes, the bus could have stopped in Fakenham if a customer did urgently need the toilet or water and First could have checked that passengers were OK. There’s all manner of logistical questions here, but there were toilet facilities in Fakenham that could have been used if a passenger really needed to. I also don’t believe that the Norwich to Fakenham bus wouldn’t be allowed to stop in Fakenham as it was technically off-route, this seemed like incorrect information from First.

In an ideal world, it’d be nice to think that the bus driver would be empowered to try and get customers back on a taxi as the journey would have been 15 minutes. Perhaps it wouldn’t have worked if there was no availability, but it would have been nice for them to try. And of course, I did have Nathan on board with me, who used to work for a bus company and it didn’t entirely warm my heart to know that his company wouldn’t have dealt with the situation like this.

That all brings me to a problem that has been ongoing with First, which is that passengers have no way of contacting them after 19:00. Twitter is turned off, there’s no obvious support line and it’s clear that the drivers were struggling to know what to do. In this situation, it wasn’t entirely problematic as passengers were safe as they were still on the bus, but it’s clear the drivers have been given no authorisation to deal with issues and passengers have no way of gaining help.

Compared to the rail network, this is a poor customer facility that First are offering, which is slightly annoying as First operate some of those rail services. Problems must happen all the time, and if you follow the link to First’s phone number, they ask that customers call between 09:00 to 17:00 and ideally between 11:00 and 15:00. That’s dead handy if your bus hasn’t turned up in the evening. Terminating phone calls at 17:00 on Friday evening and starting them against at 09:00 on Monday morning wasn’t ideal and it’d be lovely if that someone centrally who could have sanctioned a taxi or offered to pay a contribution towards it. Even if a national customer service team could do nothing practical due to circumstances, even the offer of a small voucher for future bus travel would have been useful.

Anyway, that’s my overly long post finished. I’ll add again that I wasn’t personally much inconvenienced as I wasn’t in a rush for anything, but it puts me off getting any later bus services on First. I suspect that if we’d just got a taxi ourselves then we’d have been back nearly on time and First might well have just refunded it or made a token gesture. And if they’d offered everyone say £5 each towards a taxi, I’d have been entirely happy and would have praised their customer service instead of boring everyone moaning about it.

On that note, moan over…. And, no, I didn’t need to post this….. But, what I would like at least is just for the bus drivers to be empowered to maybe offer a £10 taxi fare each without further recourse to First in limited situations such as this.