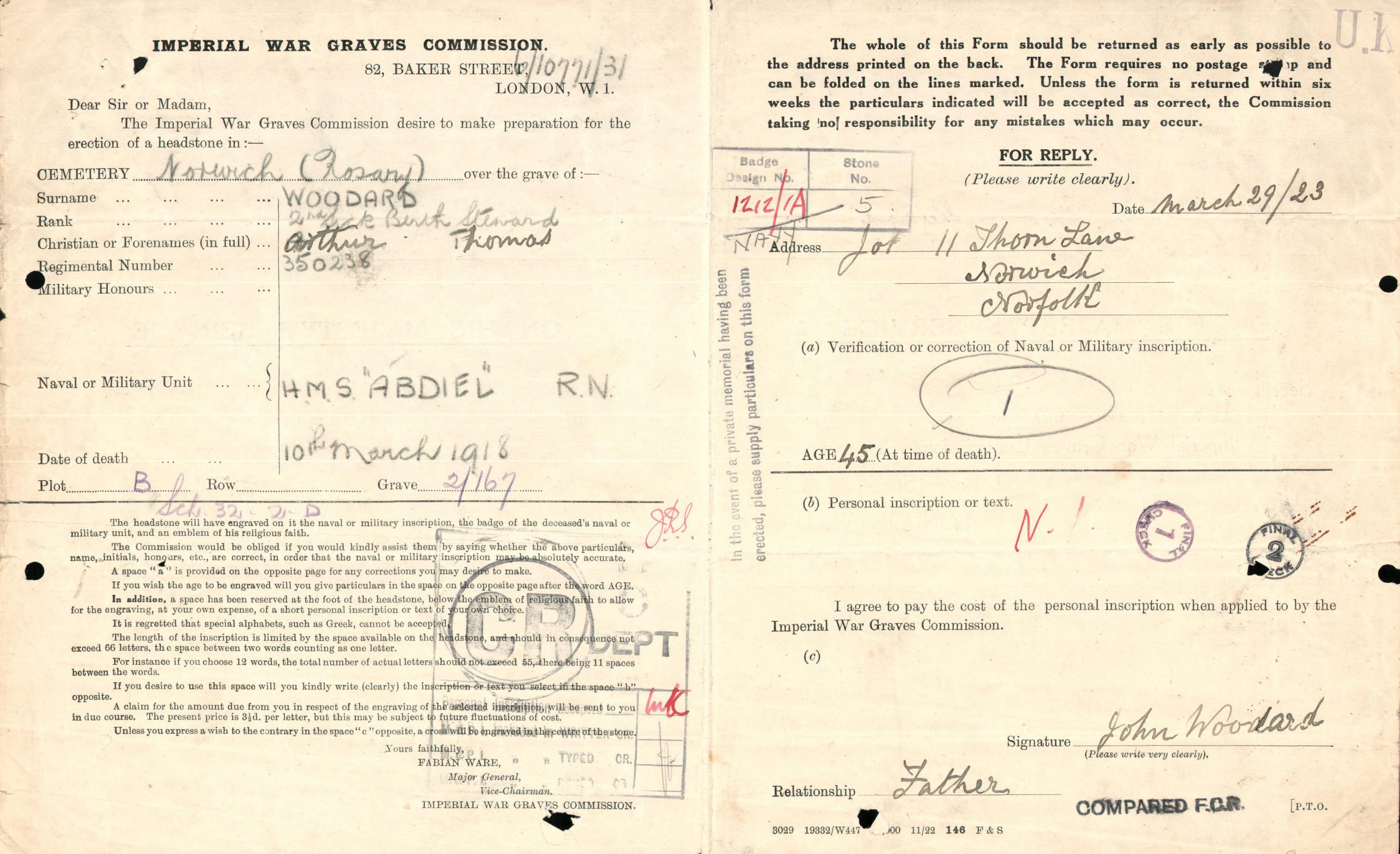

I already have a better explanation (well, longer explanation anyway) for this plan. In essence, whilst lockdown is on, I need to find ways of walking nearby to Norwich in quiet areas for my LDWA 100 training. So, I’m using GeoGuessr to pick out five random locations within a certain area which I’ve defined and then walking to them, to see what kind of story I can uncover.

Pointless? Well, yes, it is a bit. But it’s good exercise and I’m hoping to always see something new or uncover a different part of Norwich. And I’ve got Liam, Nathan and Jonathan signed up to do these walks with me as well (separately as the maximum group size is two), so I won’t have any shortage of opportunities to meander around Norwich.

Anyway, the five locations randomly selected using GeoGuessr are in the map above. I used Komoot to draw a line between them, although I didn’t always follow it if something else looked interesting nearby. And, I accept this isn’t the most exciting walking adventure possible, but it’s about all that’s safe to do at the moment, so it’ll have to do.

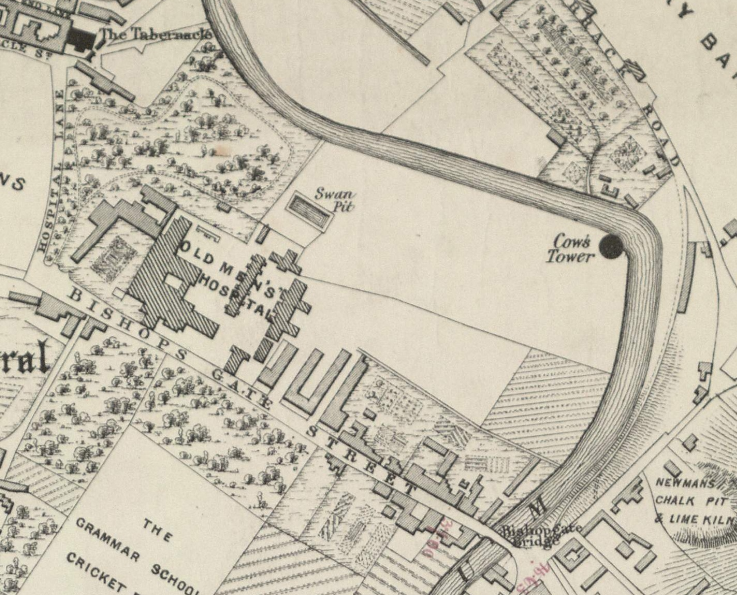

So, the start of the walk in Barrack Street, which take its name from the Cavalry Barracks which were located here between 1792 and 1963. It’s now the Heathgate estate, which doesn’t seem to get a very good press in the local media.

The route goes up the big hill of Mousehold, by the entrance to Dragoon Way, a former cavalry way.

I realised at this point that I hadn’t bothered putting on walking boots, just normal shoes, which wasn’t entirely in keeping with meandering through the mud of Mousehold Heath. This route wasn’t too bad, although there were numerous options that looked quite moist.

I had a minor problem here, as I needed to get down to the road. And there were some slightly steep elements where I could have fallen down the slope. There’s a road at the back of this photo and people walking along it, so I didn’t wish them to have their walk distracted by the sound of someone falling down a hole. So I found a more manageable route back down to the safety of the pavement and I don’t think anyone noticed. I didn’t go too far into Mousehold Heath based on this experience, sticking to firmer ground.

This is a quite wonderful building and one of the oldest in the city, at over 900 years old. It’s the city’s lazar house, or leper hospital, founded by the first Bishop of Norwich, Herbert de Losinga. After centuries of helping the ill and poor, it was closed following the Dissolution of the Monasteries and used as a barn. The city was fortunate to have had people who managed to save it from destruction in the early twentieth century and it was restored and turned into a branch library. As yet another appalling decision from the local council, they decided in 2003 to scrap this library and stop free public access to the building. It is now used by a charity to help those with learning difficulties and they no doubt do an admirable job, but it’s a great shame that the usage as a library had to stop.

This is St. George’s Catholic Church on Sprowston Road. Simon Knott, who writes in detail on Norfolk churches, has an appalling tale about the unfriendliness of this church. I’ve never been turned away from a church and I’d be equally disappointed to be turned away in such a manner. If it was me, I’d be so annoyed that I’d stomp off whilst writing in my mind the letter that I was going to send to the Pope.

I don’t often see the word ‘Loke’ used in Norwich, another word to describe a road which come to a dead end or a narrow path.

I don’t have any interest in live music, so this is a pub that holds little relevance to me, but it has a formidable reputation for its work. There was a petition last year to keep this place going and I hope that it can continue, live music is important in pubs (albeit not the ones I visit) and it would be a shame to lose it.

Now starting to enter Old Catton, this is School Lane and appropriately this is the large former school building. It’s now the Sprowston Diamond Centre, but it was originally built as a school in 1860, soon being extended in 1873.

The Woodman pub, which I can’t say that I’ve ever been to. it was opened as a pub in the early nineteenth century and there were rumours of its closure a couple of years ago, but it’s still here.

GEOGUESSR 1 – I haven’t taken a huge amount of care in finding the exact spot of the five GeoGuessr locations in terms of matching up photos. This was the first one in Old Catton, on George Hill.

One of the things that I wanted to do on these walks was to identify some listed buildings that I’ve never noticed before. This is one, which is The Firs in Old Catton, and it was first constructed in around 1750. It has since been split into four buildings, although apparently the historic eighteenth century interior is intact.

This is the best non-pub pub sign that I’ve seen.

Taken over by Enterprise Inns in 2009, so it’s fortunate that it’s still here, this is the Maid’s Head which has been trading since around 1830. Now a Stonegate pub, I’ve never been to it, although perhaps I’ll get back here again to try the real ale (which judging from Whatpub looks a bit generic to be honest).

This is Catton Park, which wasn’t exactly the busiest today. This land was originally part of Catton Hall, which was built in the 1770s by Charles Buckle. That property is still standing, now owned by Norfolk County Council, but the land can be used by the public. The paths here were quite wet and muddy, but it’s a nice piece of open space.

Some World War Two history in Old Catton.

The Old Catton village sign and St. Margaret’s Church.

Mary Sewell is perhaps better known for being the mother of Anna Sewell, the author of Black Beauty.

Another listed building, this is the Manor House in Old Catton, built in the sixteenth century and extended in the following century.

Moving away from Old Catton, I had forgotten about this Greggs on Fifers Lane, although I’ve visited a few times before. It mainly serves the industrial units in the area, and, today it had the delight of my custom.

And a quick sausage roll, which was entirely delicious.

Norse Groups is owned by Norfolk County Council and it’s a trading company providing services to local Governments across the country. Their company sign seems to have included random bits of material that they use and I couldn’t work out whether it looked really smart or really tacky.

The sad end to the Firs pub in Norwich, which closed down in 2009 and was turned into a Tesco. At least the building is still there, but I’d rather that it was in use as a pub selling decadent craft beer.

GEOGUESSR 2 – OK, I’ve cheated here (and I can hear Nathan tutting). The actual route that got selected for me was on the NDR, which isn’t accessible to pedestrians as they annoy Norfolk County Council. So, I was going to just get a photo of it from the nearest point, but that would have involved a huge detour. So, I thought I’d get a photo of it from Norwich Airport, but it was all a bit misty. So, this is the memorial at Norwich Airport to RAF Horsham St Faith, and that’s doing me as the second point.

Well, it was open, so I went in, as if I’m traipsing out to these places I might as well take advantage of the situation.

I’ll write about this elsewhere in more detail, but the service here was welcoming, the prices were OK (although not particularly cheap) and the chips were delicious.

Sad to see the Whiffler, a JD Wetherspoon pub, all closed up. This was, until last year, their car park, but to encourage social distancing and to give them more space, they opened it up as an external seating area. I hope that change of use continues in the future.

I noticed on the side of this sign it has printed on it “Do Not Display on Drive-Thru Lane”. I suspect this is because it mentions their cheap products on the Saver Menu (the ones I keep buying) and they don’t actually want customers to be reminded of them at the point of ordering.

I’ve been meaning to visit this, hence my detour along the Boundary Road, it’s the boundary cross which was erected in the fifteenth century to mark where the King’s Way crossed the Norwich City boundary.

I was slightly annoyed at this. I saw a sign to “new cemetery” and I’m intrigued by cemeteries, so went to have a look. It transpired that this was the back of St. Mary’s Church in Hellesdon, which I hadn’t initially realised. And, the sign was a lie, as there’s a bloody great big gate which stops pedestrians getting in. Looking at old maps, there were footpaths here which allowed people to access the rear of the church, but they never made it through to the Definitive Map and the church has taken the opportunity to restrict access. Or, at least, I couldn’t find access, hence the above photo. It’s also clear that people have been trying to gain access and the fence there has been added to stop them. Personally, if I had a church (which I don’t, and I don’t intend to acquire one), I’d quite like people to go in it.

Back on the route that Nathan and I undertook a few weeks ago.

GEOGUESSR 3 – this is the reason that I went out this far, to get to Gunton Lane.

This is the Marlpit Community Garden, a seven acre plot of land that was once part of Lower Earlham Farm. Individuals now use the land for communal growing and there’s a bee area, footpaths, orchards and wild flowers.

To get back to the city centre, I ignored the Komoot suggested route and just went along Marriott’s Way, which was much quieter than I had expected.

One of the sculptures along Marriott’s Way, a former railway line. There’s a sculpture every mile along the route, this is the second one along which was installed in 2009, designed by John Behm and Nigel Barnett.

The former inspection platforms at the engine shed at the now closed Norwich City Station.

I’m always sad to see railway lines closed, this is the site of Norwich City Station which closed to passengers in 1959.

This is a listed structure, a urinal which was designed by AE Collins, the city engineer, in 1919. It’s the oldest surviving concrete urinal in Britain and the city council now use it for people to graffiti on.

The walk back into Norwich covers areas that I’ve written about already, but I hadn’t noticed these flood level markers at New Mills Yard before.

Some information about St Giles’s Street that I hadn’t noticed before.

GEOGUESSR 4 – the fourth location was Norwich City Hall, a building that destroyed much local heritage when it was constructed in 1938. I quickly popped into Tesco on Westlegate at this point to buy their reduced sandwiches…..

Walking past St. Julian’s Church, which I wrote about the other day.

Going onto King Street, this is Dragon’s Hall, sadly no longer open to the public, but this was a museum that wasn’t allowed to continue. It’s a Grade I listed building, with much of the current structure dating to the fifteenth century, although there is evidence of a ninth century structure having been here before. I hope that this building can in future be repurposed and brought back into public use, as it’s currently been taken over by the National Centre for Writing.

Work has started this week on the development of the former Ferry Boat Inn site by the River Wensum. I don’t see why the developers couldn’t have restored the pub element in their project, but apparently the building was too damaged (although not too damaged to allow its conversion into two residential properties). It’s positive to see this area being brought back into usage though, it’s been derelict for over a decade now.

GEOGUESSR 5 – and the final point of the day, Norwich City Football Club. The club was founded in 1902 and they’ve played at this Carrow Road site since 1935.

And that was the end of the walk. It was fourteen miles and took me just under five hours, although I did keep getting distracted along the way, hence the slow pace. I’m not sure that there’s any great unifying story for me to tell here, but I discovered some things that I didn’t know existed in Norwich. And I like this element of random, it gives a purpose to an expedition, as otherwise there’s no way I’d have been bothered to have walked so far.