Part of my Streets of Norwich project…. I hadn’t forgotten about it, and perhaps in 2021 I might finish it.

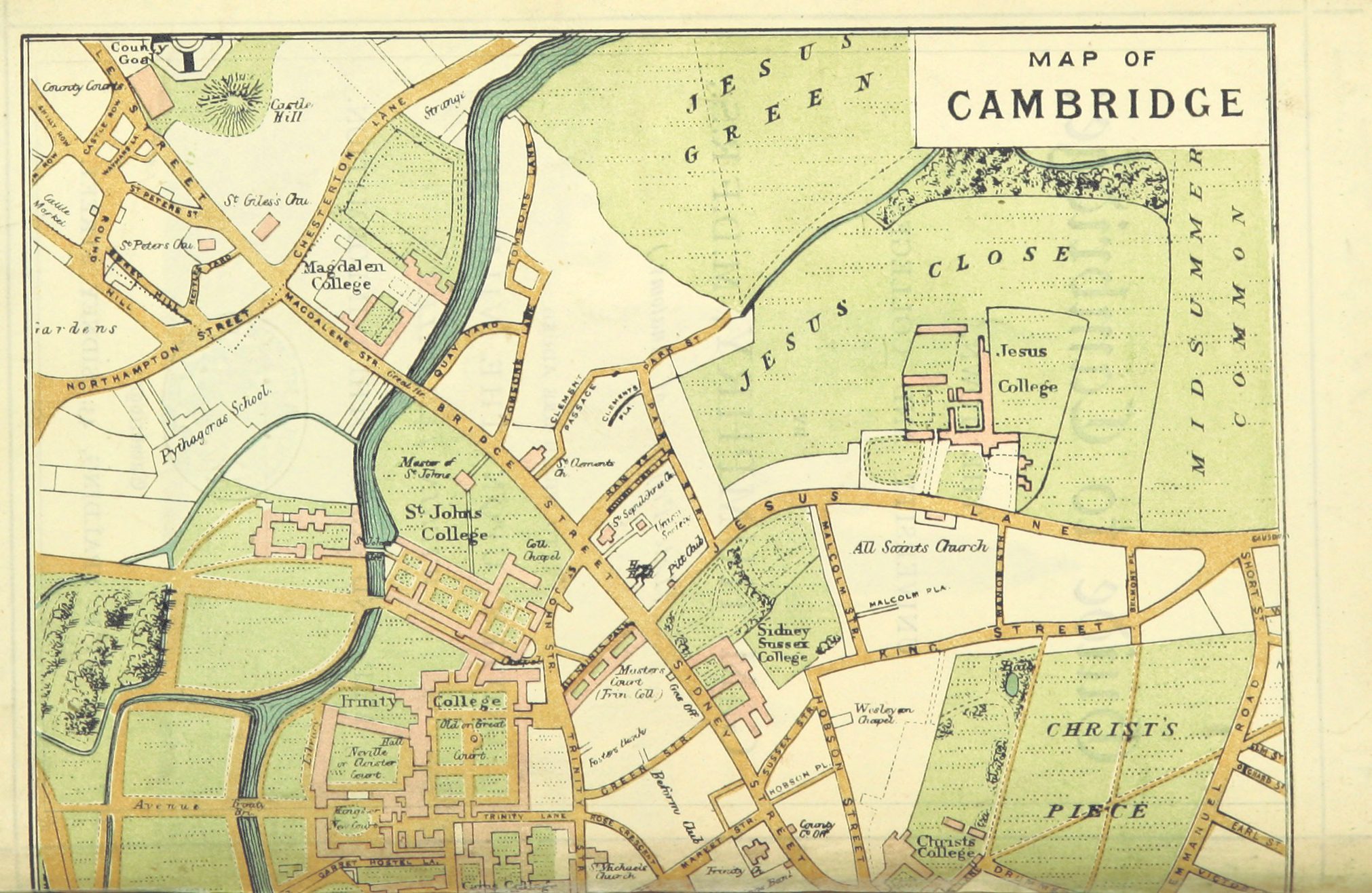

This is Fishers Lane (Fisher Lane on the above map) which is between Pottergate and St. Giles Street. The map above is around 100 years old, the one below is around 150 years old and maps in general alternate between Fisher and Fishers Lane (as well as Fisher’s Lane).

Clicking on the image will make the map larger and it’s possible to see there were two courts off this street, the Bear & Staff Court and Roache’s Court.

The police didn’t like the pub called the Bear & Staff and in 1908 they complained to magistrates that the customers were of a lower class and criminals frequented it. Its location, tucked away in that court, does give it a feel of being somewhat of a vibrant location. The pub sadly closed in 1910, if it had survived I imagine it would have been one of Norwich’s quirkiest drinking options. Unfortunately, the entire street has been lost, although George Plunkett was able to get a photograph of the southern side in 1938.

The entrance to Fishers Lane from St Giles Street and that is St Giles Hotel on the left hand side.

Sadly, most of the historic interest of this street has been lost, the entrance to Bear & Staff Court would have been around where the two buildings on the left hand side join. The ugly cladded building is Vantage House, which was used as offices by the council, but the owners have been granted permission to turn it into 44 flats. That cladding was added by Harley Facades, better known now perhaps for their work on the Grenfell Tower refurbishment. I’m not sure why the council have granted permission for it to be turned into flats (although I think they might have had limited powers to stop it as it’s a conversion), it’s not a pleasant building and I’d have thought it would have been better to demolish it and replace it with something more uniquely designed and purpose built for housing.

Looking back to St Giles Street.

The buildings on the other side of the road are older and are former warehouses, although nothing on the street is listed (other than the properties facing onto St Giles Street).

Standing on Pottergate looking back up the hill.