This was our tenth walk in preparation for the 2021 LDWA 100.

WALK NUMBER: 10 (Finding the Source of the River Yare Part 2)

DISTANCE COVERED: 14.7 miles

NUMBER OF NATHAN’S FRIENDS WE “ACCIDENTALLY” BUMP INTO: 1 (might have been someone I knew)

SUFFICIENT BEER CONSUMED: No (all the pubs are shut)

PUBS VISITED: 0 (not through choice)

WEATHER CONDITIONS: Dry

ATTACKED BY ANIMALS: No

NUMBER OF SNAKES SEEN: 0

The eagle eyed reader will note that the 14.7 miles has been split across two posts. Some might suspect that this was because I couldn’t be bothered to post about the entire walk in one go, but I repeat that it was to add suspense. Or something like that….. Anyway, the first post ended with Nathan faffing about crossing a puddle.

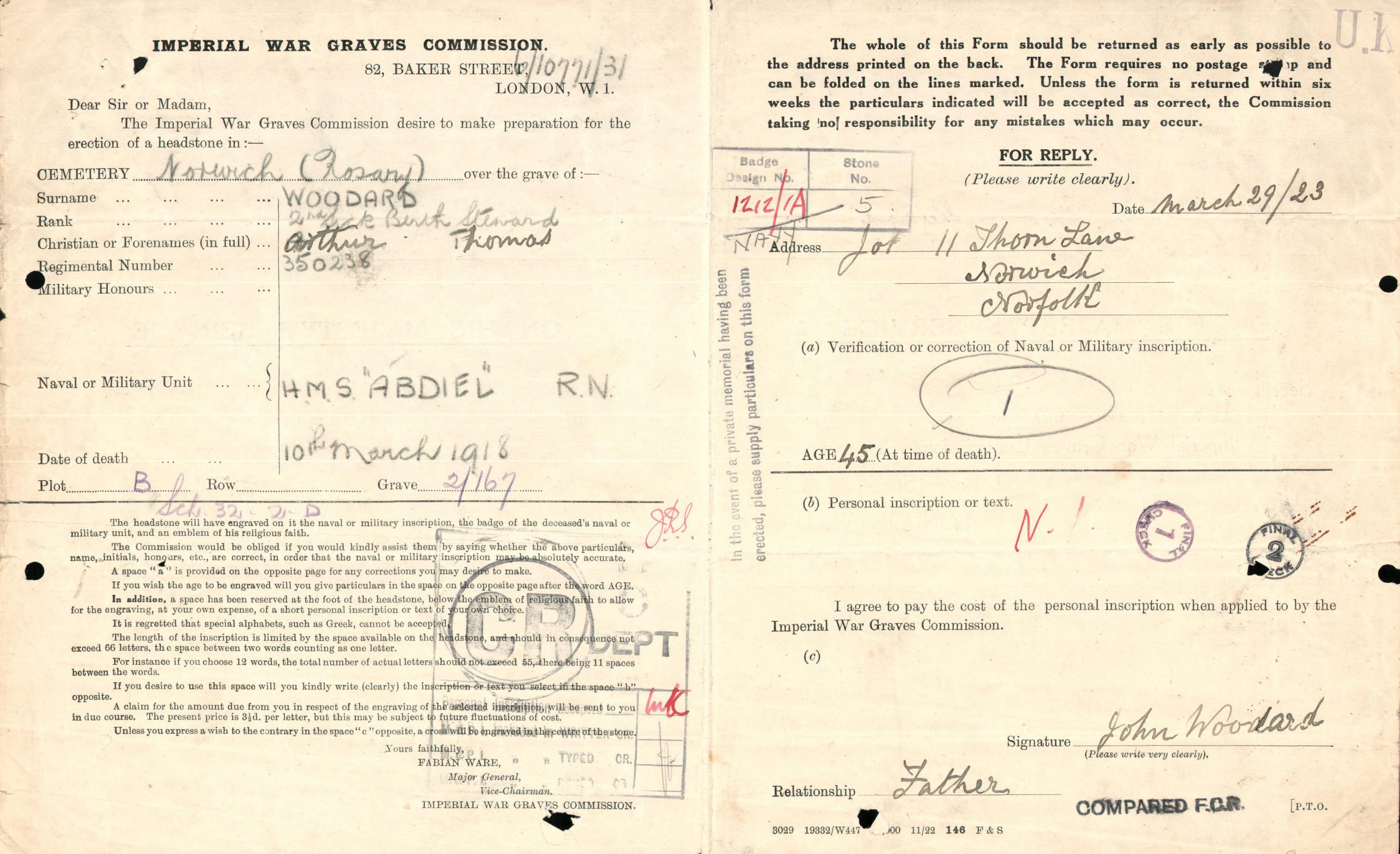

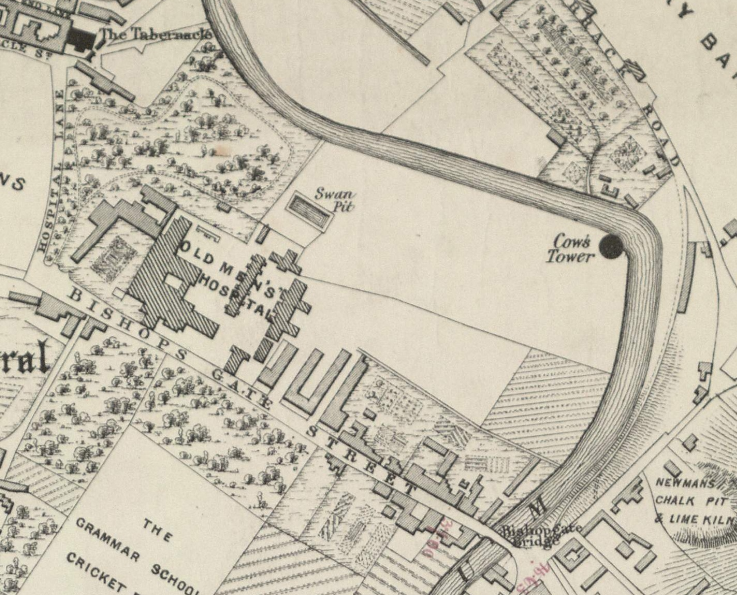

At the moment, we’re on the right of the above map (moving left) and we were able to track the river for the first stretch.

A frosty scene….

We were able to continue by the river, although there were stretches that were particularly muddy. Slightly amazingly, neither of us fell over during the day. There weren’t that many other walkers along this little stretch, but that’s probably because they didn’t feel that sludging through this was ideal entertainment.

Long before this health predicament I had been planning to be in Las Vegas at this time, accidentally ordering a sack of burgers at White Castle. As an aside, this is why the United States is so exciting, where else can you buy a sack of burgers? And yes, this is a real thing, anyone interested can Google it. I could have been playing video poker in Excalibur, getting free beer and popping into Banger Brewing later in the day after a ride on the Deuce (not Douce). Instead, I was walking on mud, but I think I was still enjoying it.

Here we came across a little problem. That’s the path.

The Yare had entirely burst its banks at this point and the footpath wasn’t even visible, let alone walkable. It’s evident in the map image, we could no longer walk by the river and instead had to head back inland (not sure that’s the right word there, but it sounds more exotic) towards Eaton Golf Course.

Instead and so no-one feels that they’re missing out, here’s a photo of that exact stretch of flooded route that we walked last June. It was less moist then.

Don’t fear, I didn’t linger on the railway line.

On the above map, the blocked footpath meant we couldn’t track the river, but we did walk back down to it (on the left-hand side) to try and explore it a little bit. This was always a closed loop we’d have to go back up from, but it was part of our policy of walking by all the bits of river that we could. I got a bit muddled up here and tried to walk the wrong way along a path that looked interesting, and I’ll have to credit Nathan for noticing that I was trying to go back in the same direction we’d just walked from. He can be quite observant.

For anyone who wants to see the map click on the above image (and to read about how one child said this area was “very wild”) to see where the footpath was meant to be.

Nathan set off to explore the area and I pretended that I was Stewart Ainsworth from Time Team. For those who never watched that, Stewart is the guy who looked at the wider environment, often looking for evidence of raised land where historically people would have walked so that they didn’t get their feet wet. To cut a long story short, all the terrain was flat, I forgot that I was in Norfolk. So whilst Nathan was sinking into mud, I concluded this strategy of mine was failing. It wasn’t possible to get to the river here. Well, not without sinking anyway and although I wondered what Nathan would look like if he sank three feet into the ground, I thought it would all be too much hassle to fix. And that kid was right (not Nathan who is nearly 30, I meant the one who was featured on the sign), it was very wild around here.

After spending some time helpfully smashing the ice to help the local wildlife (I’m not sure we worked out what help we actually were, but there’s something satisfying about making a hole in ice), we decided we’d seen enough of this meadow.

We (well Nathan did, I was looking for a big stick to break the ice with) did spot the river and although it’s hard to see, it’s the water course at the back of this photo. We only knew it was the river as we could see it flowing at some speed.

So, we retraced our steps (visible on the right of the above map) and then walked into the wealthy Norwich suburb of Eaton. We lost sight of the river at this stage, but it was nice to see civilisation again after our time in the wilderness. OK, I accept we had hardly been walking in the Amazon, but it’s all relative and I have to try and make a walk around Norwich sound as exotic as possible.

This is St. Andrew’s Church in Eaton and it’s rare to see a thatched church in the area around Norwich. The bulk of the church dates from the thirteenth century and there are some wall paintings inside which I’ve looked at before and had no idea what they were portraying.

I think I annoyed Nathan by applauding an extension they had put on the back as meeting my design requirements (where the old meets the new….), whereas I didn’t like the one at the church where he got married. He’s getting very protective of that church….

We might have seen someone we knew at this stage, as we saw someone waving and calling out. Then they looked grumpy and walked off before we worked out who it was. Hopefully it was one of Nathan’s friends who was annoyed and not someone that I might know. If it was someone I knew calling over, then hello 🙂

We thought at this stage that we’d pop into Waitrose. Now, given that Nathan and I are hardened walkers ready to take on the 100 in a few months, we feel that we’re competent navigators who are experienced and confident. We then couldn’t find our way into Waitrose and got entirely muddled up, which frankly wasn’t ideal. As an aside, and without being rude, whoever is in charge of signage at this Waitrose is a bloody idiot. Right, moan over.

The true measure of a shop is the quality of their craft beer selection. Although not world class and lagging behind Morrison’s, this wasn’t a bad effort. Anyway, Nathan and I decided that Waitrose was too decadent for us (I still feel I’m an imposter going into M&S, let alone Waitrose) and so we continued on our walking expedition.

This was the path at the rear of Waitrose and there is a path which leads from here to the UEA. We were a little concerned at first as this was not an ideal situation in terms of the mud, but it transpired that this was the only problematic stretch.

This is the stretch to the A11 and it hadn’t flooded at all, which was rather lovely.

I’m not a bike expert, but this could have done with a service, perhaps using the scheme promoted by the Government which nearly no-one was able to get.

The bridge looks quite ugly here with the graffiti and rickety metal structure shoved on the side.

It’s more pleasant from the other side and this is Cringleford Bridge which was built in 1520 and extended in 1780. The previous bridge had been lost to floods in 1519, which probably annoyed the locals at the time. This was once on the main road, but there’s a new road bridge on the nearby A11 to relieve the traffic on this one. Of relevance to our walk, the listed building records notes that “the southern bank of the river Yare is now the boundary of the City of Norwich”.

A previous flood level marker on the bridge. Fortunately, the water wasn’t quite that high when we meandered along the route.

The bench didn’t seem correctly proportioned to me.

This is the next stretch of the path, which sticks by the river and leads into the University of East Anglia (UEA).

This was our final stretch on this walk, and that stretch from the bridge to the lake is visible on the above map. The big lump of water is the UEA lake, with the university buildings just above it towards the top of the map.

I’ve never seen a dog entry point into a river, but it didn’t seem like a bad idea. I thought at first it was something that snakes had created for themselves, so I was pleased it was a less dangerous type of animal (although knowing someone that has been bitten by a dog recently, she might not agree).

I noticed there was a little stretch off the main path which stuck close to the river. We went down there, but didn’t get far as there was a tree in the way further down.

A little pier on the lake with the UEA buildings behind. As one of the university’s leading alumni, I didn’t note Nathan gazing longingly at the buildings, but perhaps he was inwardly excited to be back.

This is the ‘Man of Stones’ bronze sculpture designed by Laurence Edwards and installed here in 2019.

We didn’t need to cross over here for the purposes of our walk, although we might have had a little meander on the other side if it had been open.

I was quite glad that it was shut, as it’s called the Mathematical Bridge and this might have over-excited Nathan given his maths degree. I can imagine him walking over 25 times to celebrate just how mathematical it was.

It is called the Mathematical Bridge due to its construction being comprised of only straight lines and this mathematical structure is meant to surprise and delight people as the average person might think from its design that it would collapse. Anyway, it’s closed as it’s collapsing, but once they’ve fixed the foundations it’ll be open again. I hope the bridge that my civil engineer friend Liam is currently building doesn’t suffer from the same fate, but I’m sure he’s got that under control.

I wanted to carry on by the river, but it was getting muddier.

At this point, we’re on the left-hand side of the lake. The path that was too muddy to follow would have allowed us to carry on by the river, but instead we took a parallel route (well, sort of parallel) route towards Earlham.

This was too difficult to cross as the water was deeper that it looks in the photo. I know this as I tried to walk across it. Nathan, who can sometimes be more sensible than me, held back looking concerned. He was right (hopefully he won’t notice me writing that).

A bushy tree. Anyway, at this point we had gone off track and so we’ll be back soon to try and carry on along the path that we couldn’t walk this time. And then we’ll walk further down the River Yare and I can imagine how excited everyone must be to read about that……