And, just photos in this post. These are the caves located just off the A623, between Eyam and Stoney Middleton. There were numerous climbers in the area with ropes and I considered myself exceptionally brave to climb a few rocks to go and examine a cave.

Category: Eyam

-

Eyam – Name Origin

When we were in Eyam this weekend, we were debating whether it’s pronounced Eee-am or I-am. Fortunately, we checked on-line before trying either of these words on the locals, as it’s pronounced Eeem. This is what The Concise Oxford Dictionary Of English Placenames has to say about the origins of the village name:

Eyam, Derbyshire. Aiune in Domesday Book, Eyum in 1236. From Old English egum, the plural of eg, or island.

The origins of the word are likely that Eyam was an island area in between moors or marsh, with the word island in Old English being ‘īeg’.

-

Camping – Day 1 (Eyam – Cucklet Church)

We saw a map in Eyam which mentioned the Cucklet Church, an outdoor rock formation that was used for religious services when it was felt wise not to use the church to avoid the spread of the plague. We weren’t entirely sure what to expect, although a family picnicking pointed us towards the rocks where the services were held.

Families could socially distance within the rocks, and also on the open ground amphitheatre type arrangement on the edge of the valley (known as the delph), which helpfully enabled social distancing. Everything in history comes around in circles….

William Mompesson, the local priest, was one of the key figures who managed to stop some of the villagers fleeing to Sheffield to avoid the plague in Eyam, which would have only caused the disease to spread. He led the services at these rocks, apparently designed to try and inspire the residents during some trying times.

Some photos of the rocks….

And a photo from 1896.

-

Camping – Day 1 (Eyam – Village Stocks)

The stocks in Eyam date back to the late seventeenth century, so are from around the period when the plague struck the village. The stones at either end are made from gritstone, with the wooden bars resting in holes in the stone. It’s thought that they were placed here by the Barmcote Court, a local system of justice used in lead mining areas of Derbyshire.

The stocks were restored in 1951 to mark the Festival of Britain, which seems a cheery way to mark what was supposed to be such a positive event. Thanks to the Statute of Labourers law of 1351, every village in the country once had stocks, although they were used more rarely after the eighteenth century. The last recorded use of stocks was much later in the UK, coming in 1872 in Newbury, Berkshire.

And here’s a photo of what the village stocks looked like in 1919, when it wasn’t quite as obvious what they were.

-

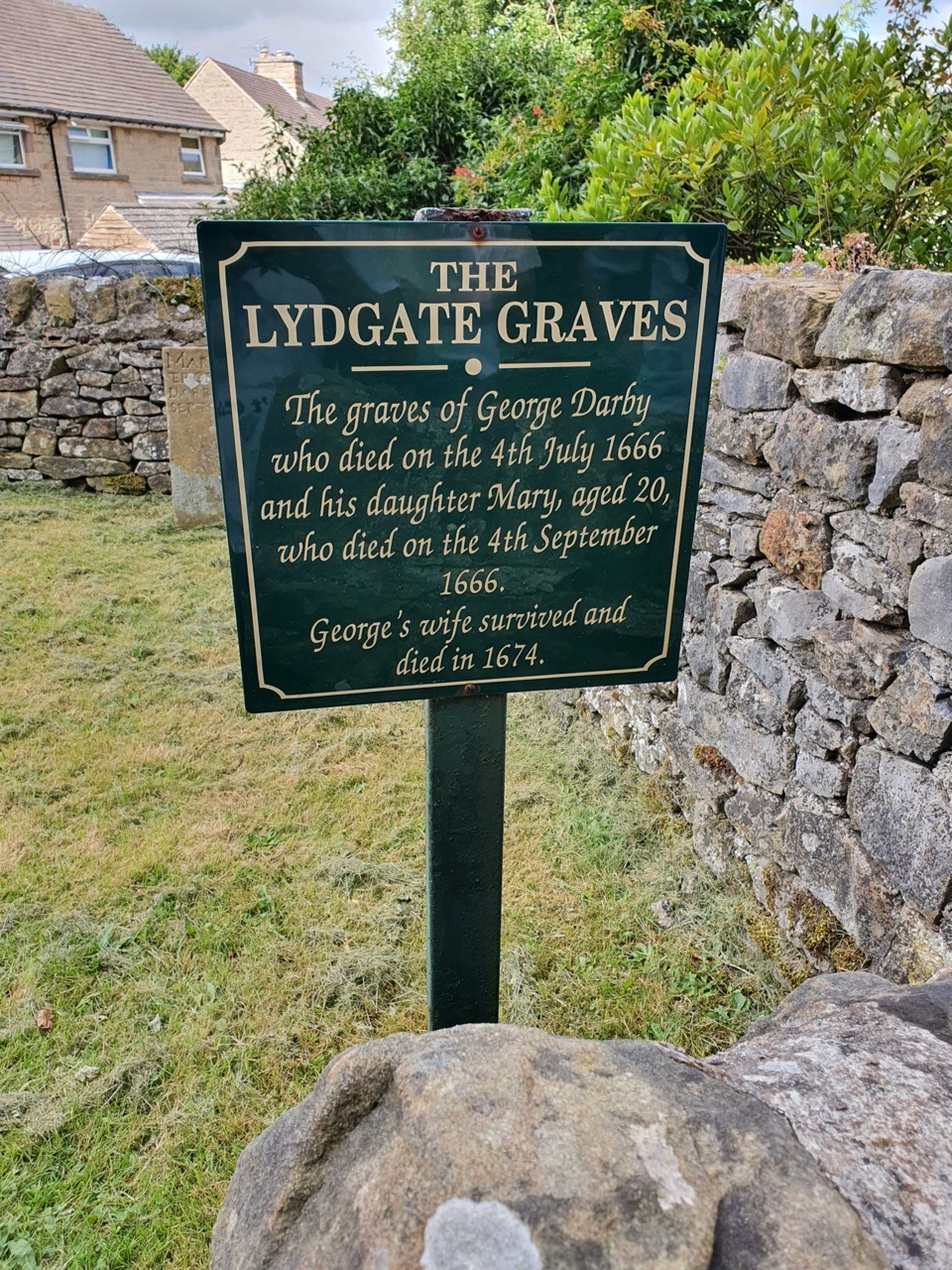

Camping – Day 1 (Eyam – Lydgate Graves)

Back in the days of the plague in Eyam, local residents were allowed to bury their dead in what was previously unconsecrated ground since the main churchyard was temporarily closed off. This enclosed area, off the road called Lydgate, is known as the Lydgate Graves site, with two burials dating to 1666.

The grave of George Darby, who died on 4 July 1666. The inscription reads “Here lyeth bvr the body of George Darby who died on July 4th 1666”. The ‘bvr’ bit is either a mistake on the listed building record, or it’s an English abbreviation that I have no clue about.

This is the grave of Mary Darby, the daughter of George Darby, who died on 4 September 1666. The inscription reads “Mary, the daughter of George Darby, dyed September 4th 1666”.

Before the plague struck Eyam, there were three people in the Darby household, George, his wife Mary and his daughter Mary. George had been born in 1610 and his wife Mary in 1615, with their daughter Mary born on 28 December 1645. George’s wife survived the plague, living until 1674.

-

Camping – Day 1 (Eyam – St. Lawrence’s Church – Sundial)

This is the sundial (click on the image to see a larger version) on the wall of St. Lawrence’s Church in Eyam, which was installed here in 1775. It’s supported by two stone corbels and was likely made by William Shaw, a local man. It’s not the most subtle of sundials given its size, but no-one could miss a church service and claim that they didn’t know the time.

The below photo shows how the sundial looked in 1919 and it’s also noticeable that the ivy has wisely been removed from the church, which avoided any similar incidents to Crostwright Church….

-

Camping – Day 1 (Eyam – St. Lawrence’s Church – George Palfreyman)

This is the grave of George Palfreyman in St. Lawrence’s Church in Eyam. George was born in Monyash, a village near Bakewell, on 1 June 1759, the son of Thomas and Mary Palfreyman. George also married a lady with the name Mary, although I can’t find out where that happened, but there is a marriage in Sheffield between a George Palfreyman and a Mary, but the birth-dates don’t match. He died on 29 March 1825 at the age of 67 (which again doesn’t quite match with being born in 1759, so I may have got something wrong here), being buried on 1 April 1825.

The gravestone also notes the burial of Peter Palfreyman, the son of George and Mary, who died on 29 January 1797 aged just 12 years old and Peter had been baptised in the church on 28 August 1785. Mary was also buried in this plot following her death in October 1828, aged 72. The Palfreyman family had come to Eyam after the plague issue of the late seventeenth century.

If anyone from the descendants of the Palfreyman family knows anything else, that’d be most welcome.

-

Camping – Day 1 (Eyam – St. Lawrence’s Church – Luke Furniss)

This gravestone is located by the side of St. Lawrence’s church, attached to the wall with iron supports. It is the grave of Luke Furniss (?-16 July 1682) and is in remarkably good condition for its age, as well as being from a period from when relatively few stones remain in graveyards.

It’s an interesting stone in its own right, the 1682 death looks like it was originally written as 167 before being changed, whilst Furniss is perhaps Furness. The positioning of the ‘th’ on his wife’s Mary’s death also looks odd. The village museum has records which suggest that Luke had moved to the village after the plague of 1665, as he wasn’t listed as a resident during this time.

-

Camping – Day 1 (Eyam – Celtic Churchyard Cross)

Located in the churchyard of St Lawrence’s Church is this nationally important Celtic cross, which is thought to date from around the ninth century according to the listing building record. Or from the eighth century if you believe the sign at the church, but the truth is, no-one really knows for sure. And what’s 100 years in something that is this old?

It’s decorated with numerous images, including the Virgin and Christ, along with an angel and trumpet. A bit has fallen off of the cross at some point, but it would have stood a fair bit taller. It also wouldn’t have originally been in a churchyard, it’s a preaching cross and the usage of these is a little unclear, sometimes there would have been some preaching going on at them, but sometimes they were more used as a market crosses. This particular cross was found abandoned in a field, its significance long forgotten, before being moved to its current prominent place in the churchyard.

-

Camping – Day 1 (Eyam – Mompesson’s Well)

What is now called Mompesson’s Well was originally used by villagers to get water (although it’s actually supplied from a stream) and it also served as a boundary stone for Eyam. It is now an important part of the village’s history as locals would leave money in the water, mixed with vinegar to avoid the spread of the plague, in exchange for goods and provisions which were left here.

The wellhead is from the seventeenth century and so is contemporary from when the village was locked down, although the iron railings and paving slabs are from the twentieth century. The well is named after William Mompesson (1639-1709), the vicar of the village, who took a major role in sealing off the village to try and limit the spread of the plague. It’s a relatively short walk from the centre of Eyam and there’s a signed path that leads off from the rear of the churchyard.

Below is the unenclosed well from a photo taken in 1919.