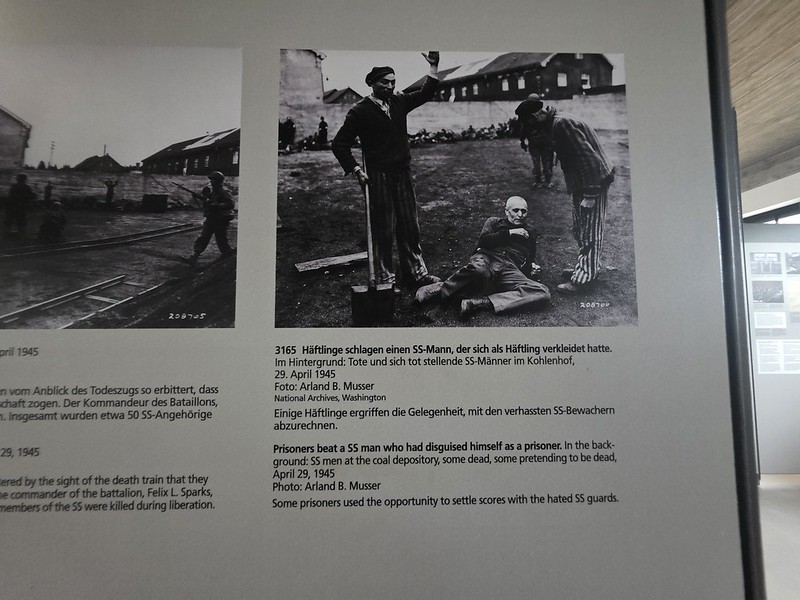

This is one of the photos that Arland Musser took when the Americans liberated Dachau on 29 April 1945, showing prisoners beating an SS man who had disguised himself as a camp inmate. It must have been traumatic for the Americans to know quite what to do, their forces had been shocked at what they’d found and would normally want to protect everyone, but here they found a site where inmates wanted revenge for the horrors which they’d gone through. There was chaos as the American military lost control and started joining in on the attacks on the German guards, it took the strength of Felix L. Sparks, the American military leader, to regain control. He later wrote:

“As I watched about fifty German troops were brought in from various directions. A machine gun squad from company I was guarding the prisoners. After watching for a few minutes, I started for the confinement area. After I had walked away for a short distance, I hear the machine gun guarding the prisoners open fire. I immediately ran back to the gun and kicked the gunner off the gun with my boot.

I then grabbed him by the collar and said: “what the hell are you doing?” He was a young private about 19 years old and was crying hysterically. His reply to me was: “Colonel, they were trying to get away.”

I doubt that they were, but in any event he killed about twelve of the prisoners and wounded several more. I placed a non-com on the gun, and headed toward the confinement area.”