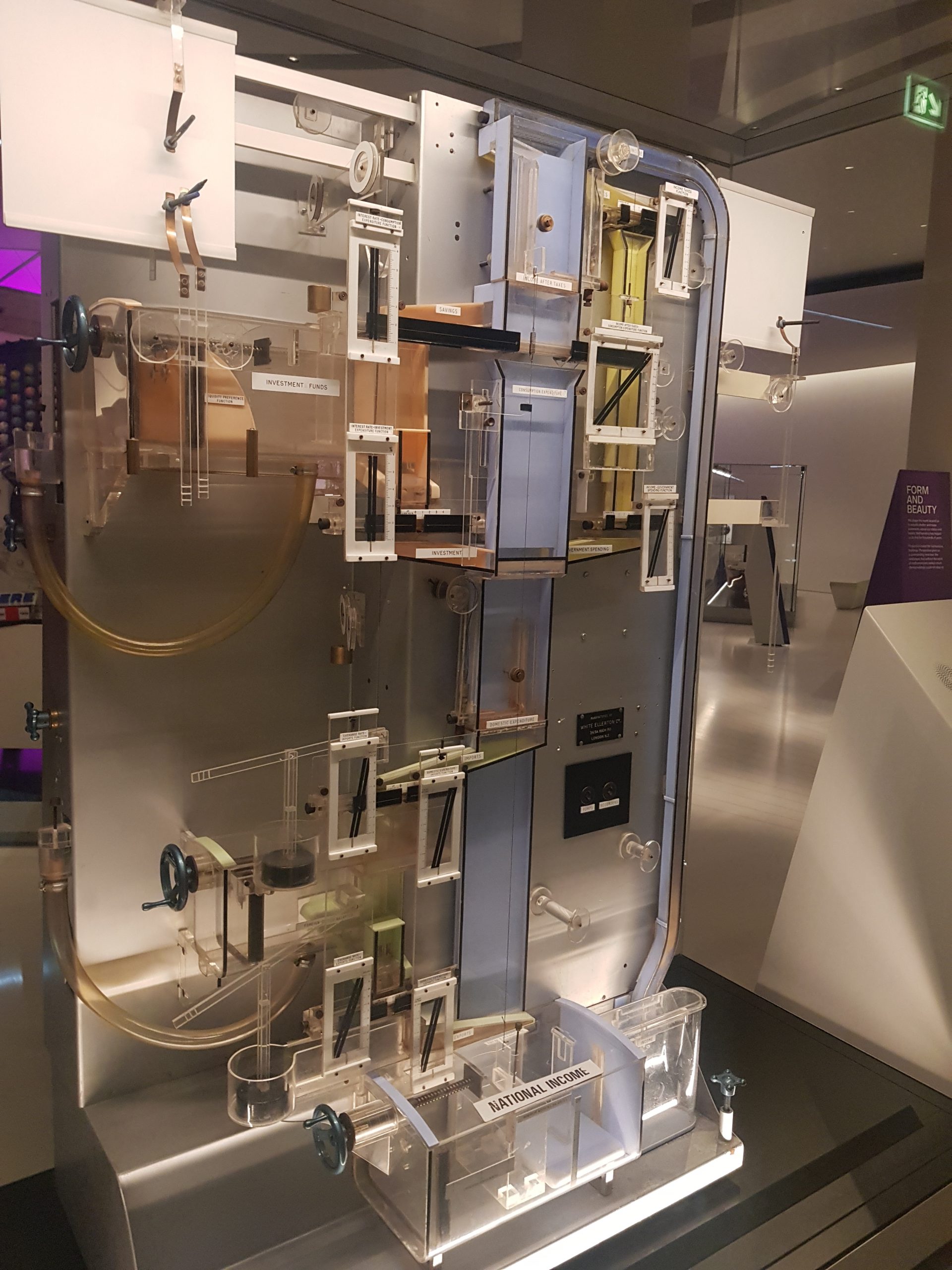

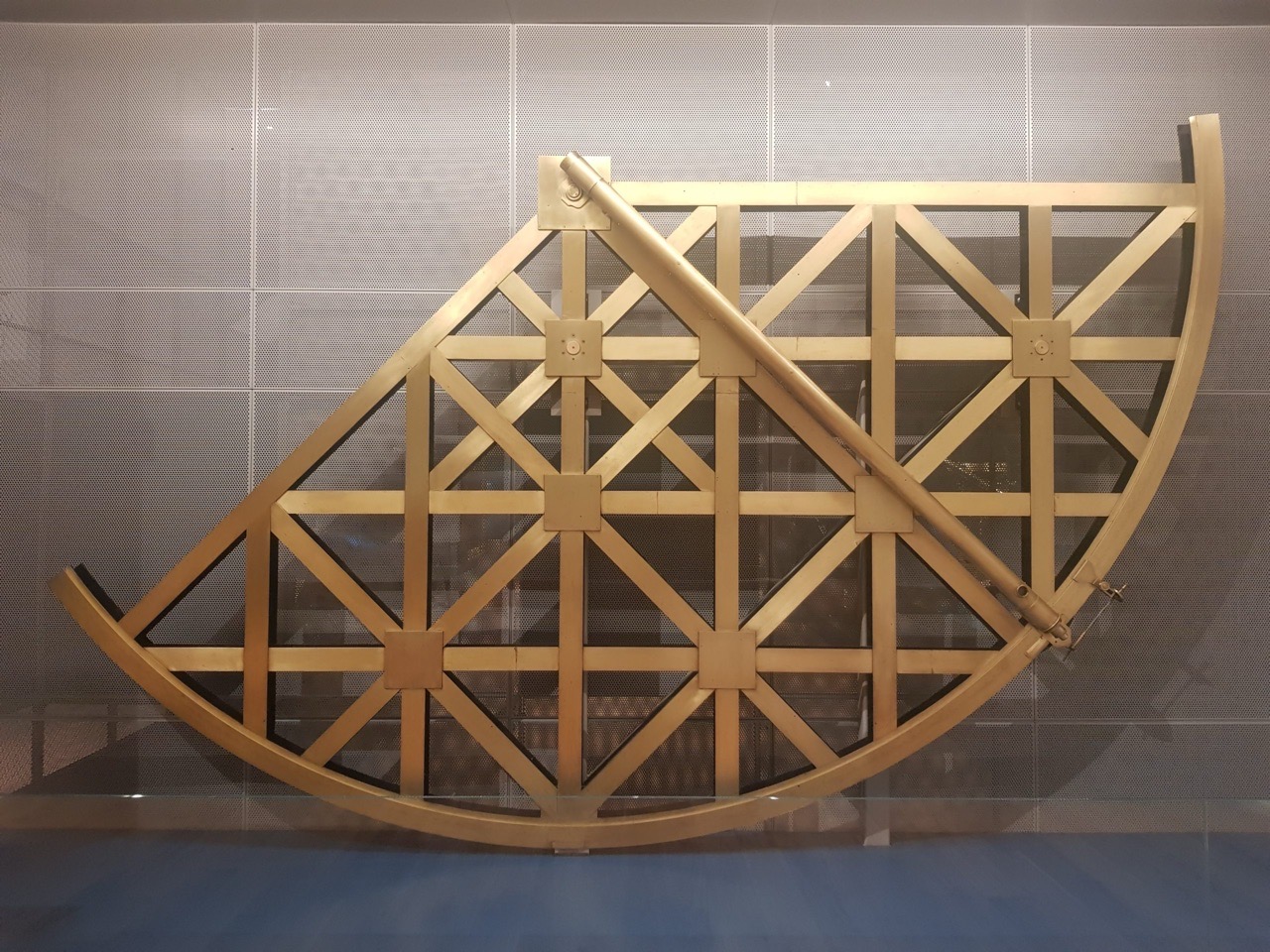

If there was any doubt that I really need to get out more, it’s my excitement at this, one of the MONIAC (Monetary National Income Analogue Computer) machines. I’ve seen photos of this numerous times before back when studying economics, and it’s a pre-computer method of measuring how the UK national economy functioned by changing various inputs. It was designed by William Phillips, the same man for which the Phillips curve is named (a link I hadn’t realised until I was enlightened by Wikipedia).

Wikipedia also tells me that there were around twelve to fourteen machines built, most of which appear to have survived and are dotted around the world. The one at the Science Museum is located in the mathematics sections and was donated to them by the LSE in 1995.

Water would flow through the machine and it was possible to work out how to try to get an equilibrium in the economy, with these models apparently being surprisingly successful.