I usually visit the British Museum three or four times a year, something which is a little difficult to do with the current virus situation, primarily because it’s shut. However, they’ve placed hundreds of thousands of images on their web-site, so this will have to do me for the moment. The images can be used non-commercially, as long as the British Museum is credited. So, this is their credit.

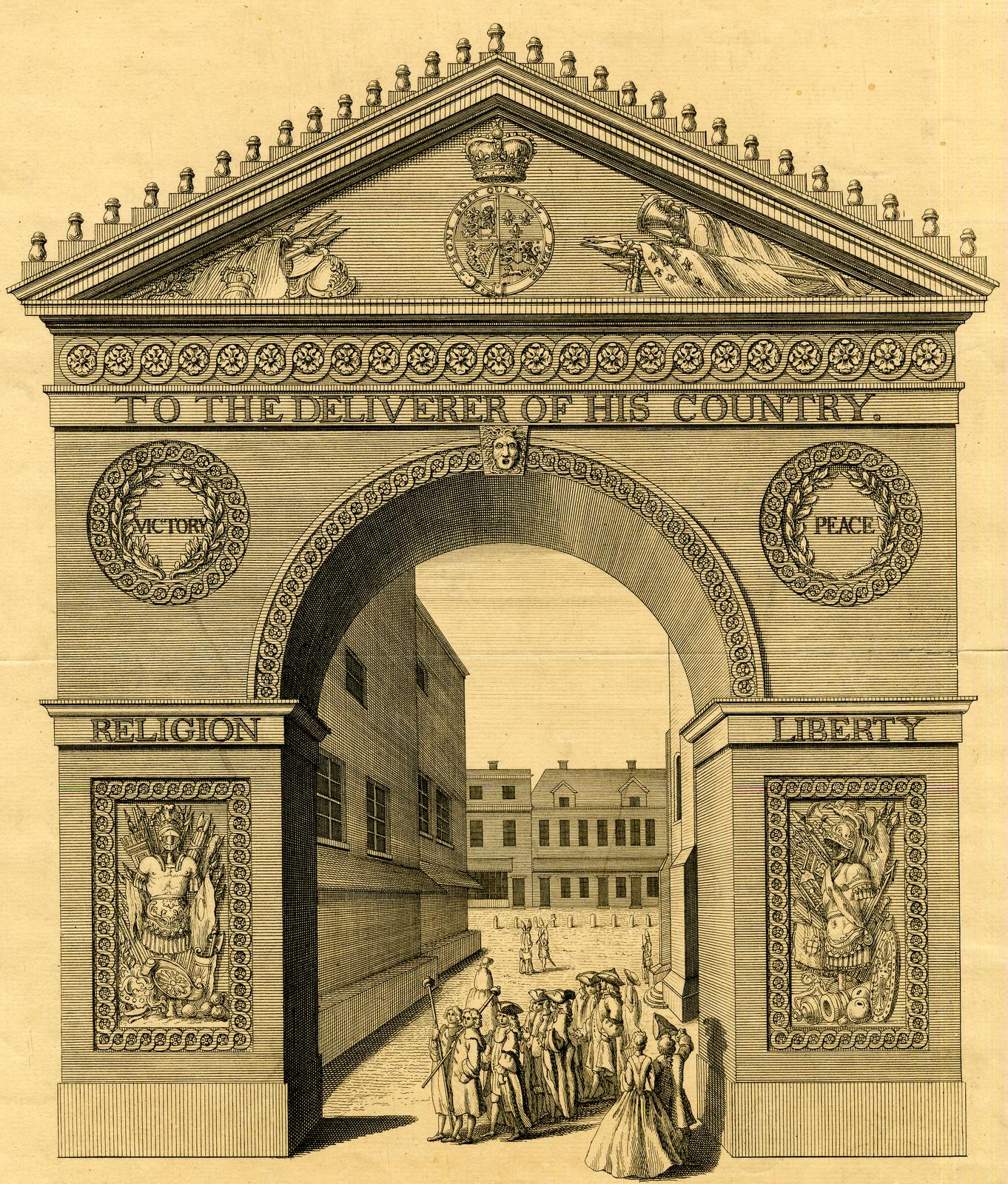

This plate is from 1787 and has the beautiful Norwich Cathedral at the rear, whilst a donkey chucks a boy off its back, kicks a dog and then gets whipped by its owner. Eventful to say the least…. The plate isn’t on display and was acquired by the British Museum in 1873 from George Mason, who was a bookseller.

I’m puzzled what that wall to the right is, there’s no obvious building on any overhead map from the period. It is though the site of whether Norwich Cathedral’s bell tower once stood, but this was torn down in the late sixteenth century and the bells flogged off. The building on the left is Norwich School’s chapel, the chantry chapel and college of St John the Evangelist which was built in 1316.

And a photo from around the same spot today. Unfortunately, no donkeys were visible to liven proceedings up.