Next on my side quest to visit every station on the Warsaw metro system is Wierzbno on the M1 line.

The station is on the first stretch of the line that opened on the network on Friday 7 April 1995 and it’s a heavily residential area. The station took its name from the local area and the etymology of ‘Wierzbno’ itself traces back to the Polish word ‘wierzba’ meaning willow tree. While the initial Ursynów sections often utilised the cut-and-cover method, the segment running through Mokotów, including the area beneath Aleja Niepodległości where Wierzbno is located, predominantly employed underground tunnelling techniques, often carried out by experienced miners. The construction took nine years in total from when they started, but Poland had gone through some rather seismic political changes during this time.

Translated, this sign says:

“Ksawerów Street – Originally the name of the estate of Ksawery Pułowski (a landowner, collector and philanthropist), established in the mid-19th century near Królikarnia, which was also his property. Over time, the name became the name of the street.”

And the street itself.

Nearby is Park Granat which takes its name from Grupa Artyleryjska „Granat”, or the “Granat” Artillery Group which was a military unit of the Polish Home Army during the Second World War.

As a general comment, the city has a lot of beautiful parks.

There’s a memorial to the Granat unit in the park which specifically highlights the unit’s courageous fight during the Warsaw Uprising in the Mokotów district, which lasted from 1 August to 27 September 1944. The group fought significant battles in this area, suffering heavy casualties (around 230 killed out of 520 who participated). Some of the bravest of the brave.

In this voyage of discovery, I didn’t realise that there was a sculpture park nearby, Park Rzeźby w Królikarni. It’s operated by the National Museum in Warsaw and they have sculptures of various ages located in this eighteenth century garden.

This marble sculpture dates from 1985 and is ‘The Kiss’ by Maria Papa Rostkowska (née Baranowska, 1923–2008). During the war, she was active in the Polish resistance and she participated in the Warsaw Uprising of 1944 (as a messenger for the People’s Army) and along with her first husband Ludwik Rostkowski she helped rescue Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto. For her wartime bravery, she was awarded the Order of Virtuti Militari, Poland’s highest military decoration.

This bronze sculpture dates from 2017 and is ‘Flor Diente’ by Xawery Wolski (1960-). The information panel notes that the work intentionally refers to the shape of a seed, tooth or flower bud, representing the unshakeable continuity of nature.

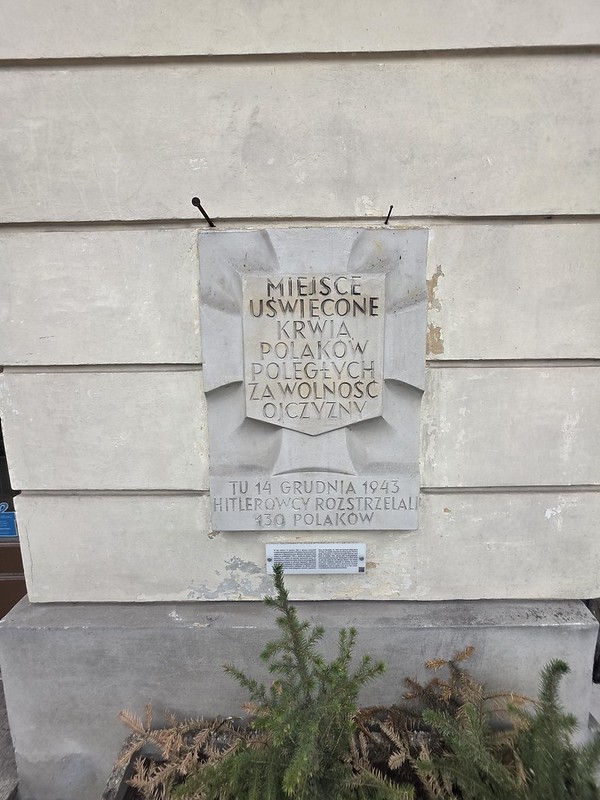

A memorial to the Home Army.

This concrete sculpture dates from 1935 and is ‘Wild Boar’ by Stanisław Komaszewski (1906-1945). He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw and exhibited internationally, but his career was brought to a premature end due to the Second World War and much of his artwork was destroyed during the conflict. He fought in the Warsaw Uprising and was arrested and then imprisoned in Dachau concentration camp and from there he was transferred to the Natzweiler-Struthof subcamp in Mannheim-Sandhofen, Germany, where prisoners were subjected to forced labour under brutal conditions at the Daimler-Benz factory. He died there on 24 January 1945 at the age of just 38.

This granite sculpture dates from 1887 and is ‘Dog’ by Edouard-Léon Perrault (1828-1888). It was acquired by the museum just after the end of the Second World War and either this, or a copy, was displayed at the Salon in Paris in 1887.

The palace here was destroyed during the Second World War, but was reconstructed and in 1965 it opened as a museum dedicated to Xawery Dunikowski.

View from the rear of the palace.

The back of the palace, it’s very English country house and when the gardens were laid out originally that was their intention.

This granite sculpture dates from 1974 and is ‘Horizons’ by Magdalena Więcek (1924-2008). Born in Katowice, she studied painting and sculpture after the end of the Second World War, first at the State Higher School of Visual Arts in Sopot (1945-1949) and then at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw (1949-1952) where she studied under Franciszek Strynkiewicz. Her early works in the 1950s were created during the Socialist Realist period and included figurative sculptures like Górnicy (Miners) and Matka (Mother). The information panel notes that an important aspect of perceiving the sculpture is how it changes along with the movement of the observer.

An old bridge which leads to the palace.

The old external wall of the palace.

Back into the network.

The interior and this is one of stations that was built as a civilian shelter in case some sort of global war broke out. That proved expensive and was dropped from later sections of metro building.

The station map.

It’s not the most decorative, but it’s functional.

The station sign.