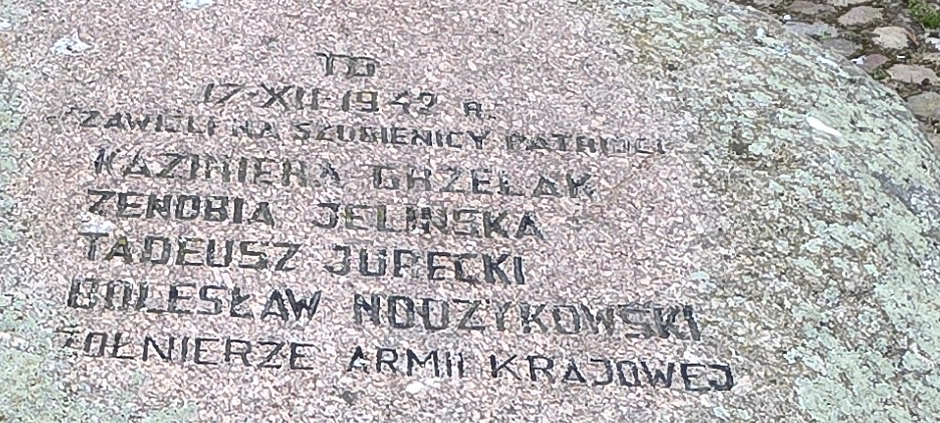

Located in the grounds of Ciechanów Castle, this is a memorial to four members of the Polish Home Army who were hanged here on 17 December 1942. The translation above refers to the “patriots hanged on the gallows” and the four killed were:

Kazimierz Grzelak

Zenobia Jelińska

Tadeusz Jupecki

Bolesław Noużykowski

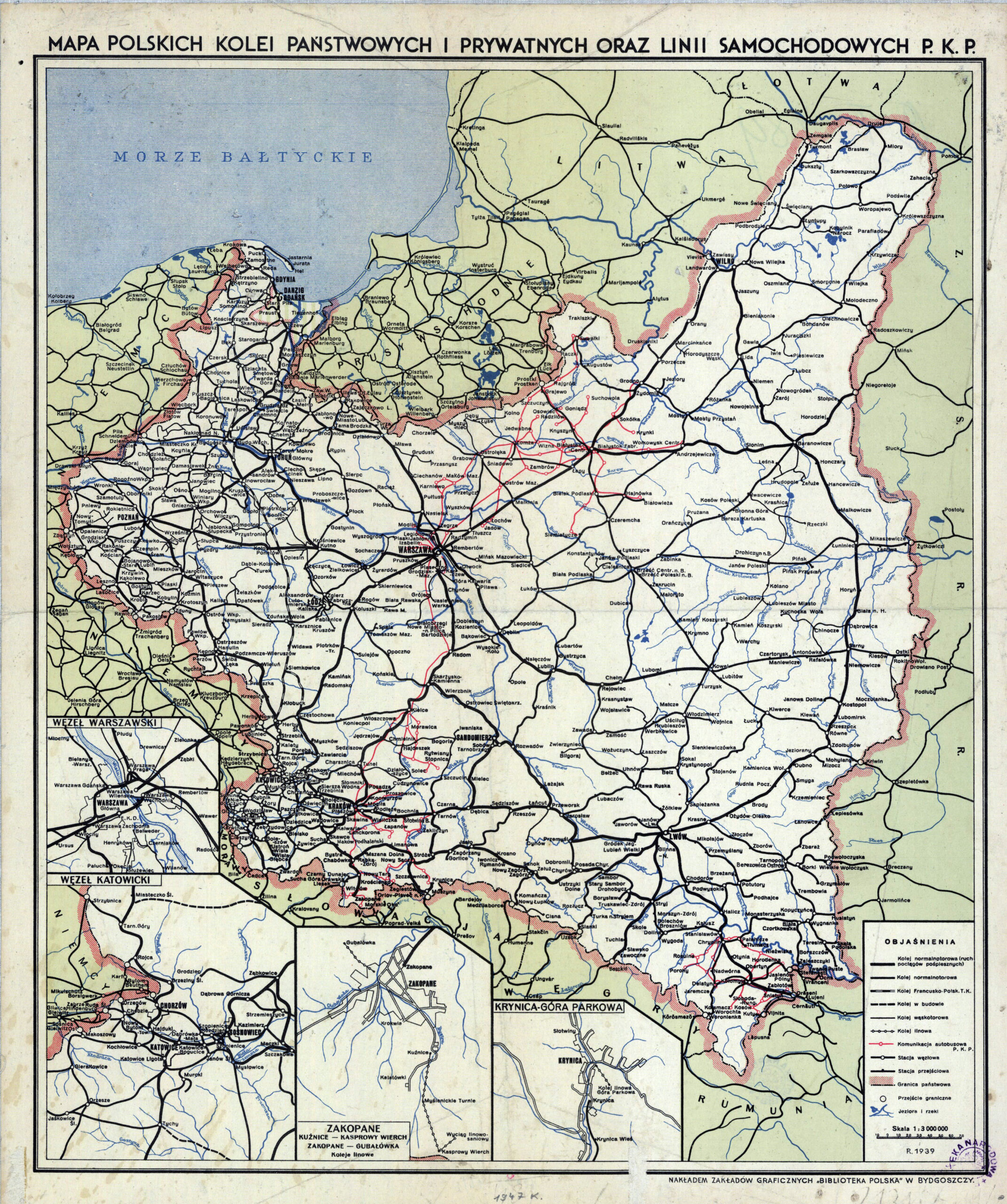

This was all a planned process and, on 17 December, German occupation authorities carried out simultaneous public executions by hanging in four key towns of the Regierungsbezirk Zichenau: Ciechanów, Mława, Przasnysz, and Pułtusk. These acts were not isolated incidents but part of a wider, centrally planned operation designed to decapitate the leadership structures of the Polish underground, specifically the Polish Home Army (Armia Krajowa – AK), and to terrorise the local Polish population into submission. The executions took place during a particularly harsh winter, marked by temperatures plummeting below -10°C, coinciding with German military setbacks on the Eastern Front and intensified, often brutal, requisitioning campaigns, such as the notorious collection of winter clothing (“zbiórka kożuchów”), from the Polish populace.

The four individuals publicly executed by hanging in the courtyard of Ciechanów Castle on December 17, 1942, were confirmed members of the Polish Home Army , the dominant resistance organisation in occupied Poland that caused such havoc to Nazi occupation. Their names were Kazimiera Grzelak, Zenobia Jelińska (using the pseudonym “Teresa”), Tadeusz Jurecki (using the pseudonym “Wrona”), and Bolesław Nodzykowski (using the pseudonym “Mały”).

Kazimiera Grzelak (1912-1942)

Born in 1912 , Kazimiera Grzelak had roots in the Tarnów region, her mother hailing from Siemiechów. After completing commercial school in Krakow, she settled in Ciechanów in 1937. Before the war, she found employment working for Franciszek Trzeciak, the deputy Starost (county administrator) of Ciechanów. In 1939, she married Władysław Grzelak, a local Ciechanów butcher. Their daughter, Maria, was born in 1941. Almost from the beginning of the German occupation, Kazimiera and her husband joined the underground, initially the Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Union of Armed Struggle – ZWZ), which later formed the core of the Home Army (AK). Within the resistance structure, she served as a liaison officer (łączniczka) for the AK’s Ciechanów district. Some sources also identify her role as distributing underground press (kolporterka prasy). In late August 1942 , Gestapo officers raided the Grzelaks’ home on Płońska Street. Their arrest stemmed from betrayal as a Polish woman reportedly accompanied the Gestapo and pointed out their exact address. Kazimiera was separated from her husband and subjected to harsh interrogation and torture at the Gestapo facilities in Ciechanów and Płock. Accounts emphasise her remarkable resilience and she refused to divulge the names of fellow underground members, reportedly earning the grudging label “Twarda Polka” (Tough Polish Woman) from her German captors and she consciously took the blame herself in an attempt to shield her husband. I suspect that a lot of German Nazi officers were surprised and entirely not delighted by just how brave so many Poles were. Subsequently, she was imprisoned in the notorious Działdowo transit and concentration camp (KL Soldau). Her husband, Władysław, met a tragic fate, being sent first to KL Soldau, then to Auschwitz, and ultimately dying in the Dachau concentration camp in 1944.

Zenobia Jelińska (1903-1942), ps. “Teresa”

Born in 1903 , Zenobia Jelińska hailed from the nearby town of Przasnysz. Within the underground, she operated under the pseudonym “Teresa”. Her involvement in resistance activities predated the full formation of the AK. She was a member of the K-7 diversionary organisation, having received training in Modlin as early as May 1939, even before the outbreak of war. During the occupation, she served as a vital courier (kurierka) for the ZWZ-AK Przasnysz district, maintaining communication lines along the critical Przasnysz-Ciechanów route. Furthermore, she demonstrated leadership by heading her own women’s section within the local AK structure. Her active role placed her at significant risk, leading to her arrest on September 8, 1942. Like Grzelak, she was subsequently imprisoned in both Płock and the Działdowo camp (KL Soldau).

Tadeusz Jurecki (1920-1942), ps. “Wrona”

Tadeusz Jurecki was born in 1920 and came from Grudusk or the adjacent village of Pszczółki Szerszenie. He was a young man, identified as a student at the Gymnasium (secondary school) in Ciechanów. His chosen pseudonym in the underground was “Wrona” (Crow). Despite his youth, Jurecki held a position of significant responsibility within the local resistance network. Most sources identify him as the Head of Intelligence (Szef Wywiadu) for the Home Army’s Ciechanów district , although a few mention Head of Communications. His family was also involved in the resistance; his sister, Joanna Jurecka (who used the alias “Teresa,” potentially causing confusion with Zenobia Jelińska’s pseudonym), was also active. Tadeusz Jurecki was arrested by the Germans in August 1942.

Bolesław Nodzykowski (1905-1942), ps. “Mały”

Born on January 16, 1905 , Bolesław Nodzykowski was from Pułtusk. He used the alias “Mały” (Little One). Nodzykowski brought valuable military experience to the resistance. Before the war, he served as a non-commissioned officer (plutonowy, equivalent to sergeant) in the 13th Infantry Regiment (13 pp), which was garrisoned in Pułtusk. Leveraging his military background and connections within the former regiment and the local rural community, Nodzykowski became a key organiser of the underground in his area. He served as the Commandant (Komendant) of the ZWZ-AK Pułtusk District (Obwód Pułtusk, code-named “Pstrąg”) until his arrest in mid-1942. The Pułtusk AK district was noted for having a particularly high concentration of NCOs from the pre-war 13th Infantry Regiment among its members. Nodzykowski was arrested by the Gestapo on September 10, 1942. He was subsequently held in prisons in Pułtusk and Płock before being transferred to KL Soldau (Działdowo). For his service and sacrifice, Bolesław Nodzykowski was posthumously awarded the Cross of the Home Army (Krzyż Armii Krajowej).

This was explicitly intended as a “pokazowa egzekucja”, a show execution, designed to instill fear and deter any further resistance among the Polish population. To ensure maximum impact, German forces forcibly rounded up residents from Ciechanów and the surrounding villages, compelling them to witness the hangings. Accounts suggest a crowd of at least 2,000 people was assembled in the castle courtyard. Some reports mention the presence of the victims’ families , and one particularly harrowing, though perhaps difficult to verify precisely, account claims that Kazimiera Grzelak’s one-year-old daughter Maria was among the unwilling spectators. The atmosphere was described as one of profound cold, fear and tension, with witnesses reportedly murmuring curses against the perpetrators and prayers for the condemned

Before the execution commenced, the formal verdict was read out, translated for the crowd, accusing the four AK members of engaging in conspiratorial work against the German state and collaborating with partisans. As they faced their final moments, the condemned displayed remarkable courage and patriotism in a way that so many Poles did during the Second World War. Eyewitness accounts consistently report that they issued a collective, defiant cry: “Niech żyje Polska!” (Long live Poland!). One account adds a grim detail: a German official allegedly kicked the plank or support from beneath their feet just as they began the second shout, cutting off the word “Polska” mid-utterance.

A significant and well-documented incident occurred during the execution, involving a local Polish farmer named Roman Konwerski from the nearby village of Kąty. The Gestapo officer supervising the execution, identified by witnesses as Ernest Wolf (nicknamed “Kopikostka”), apparently decided to amplify the horror and humiliation by forcing a Pole to act as the executioner. He singled out Konwerski from the crowd and ordered him to place the nooses around the necks of the condemned. Konwerski, despite the immense pressure and danger, refused. His defiant words, “Braci swych wieszać nie będę!” (I will not hang my brothers!), echoed through the courtyard. This act of profound moral courage had immediate and severe consequences for Konwerski. He was instantly beaten by the Germans, arrested on the spot , and incarcerated in the police prison in Ciechanów. After enduring several weeks of brutal interrogation, he was deported, likely first to KL Auschwitz and then transferred to the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp complex. According to official records from the Arolsen Archives, Roman Konwerski was shot and killed in the camp on July 29, 1943, allegedly during an escape attempt – a common Nazi euphemism for murder.

In the immediate aftermath of the execution, the bodies of Kazimiera Grzelak, Zenobia Jelińska, Tadeusz Jurecki and Bolesław Nodzykowski were treated with contempt. They were taken down and buried unceremoniously in a common grave at the local Jewish cemetery (kirkut). It was only after the war, in 1945, that their remains were exhumed and given a more dignified burial.

There is an annual ceremony held on 17 December in the castle’s courtyard to remember the bravery and courage of these five Polish patriots, but it’s hard today to imagine the terrors that took place here.