This is primarily a large winged altarpiece which is on display in the museum, although the actual large winged altarpiece bit is being restored and so only the base is on show. Formerly housed in Leipzig Lausen church, it dates to around 1500 and the full arrangement looks really quite impressive in photos.

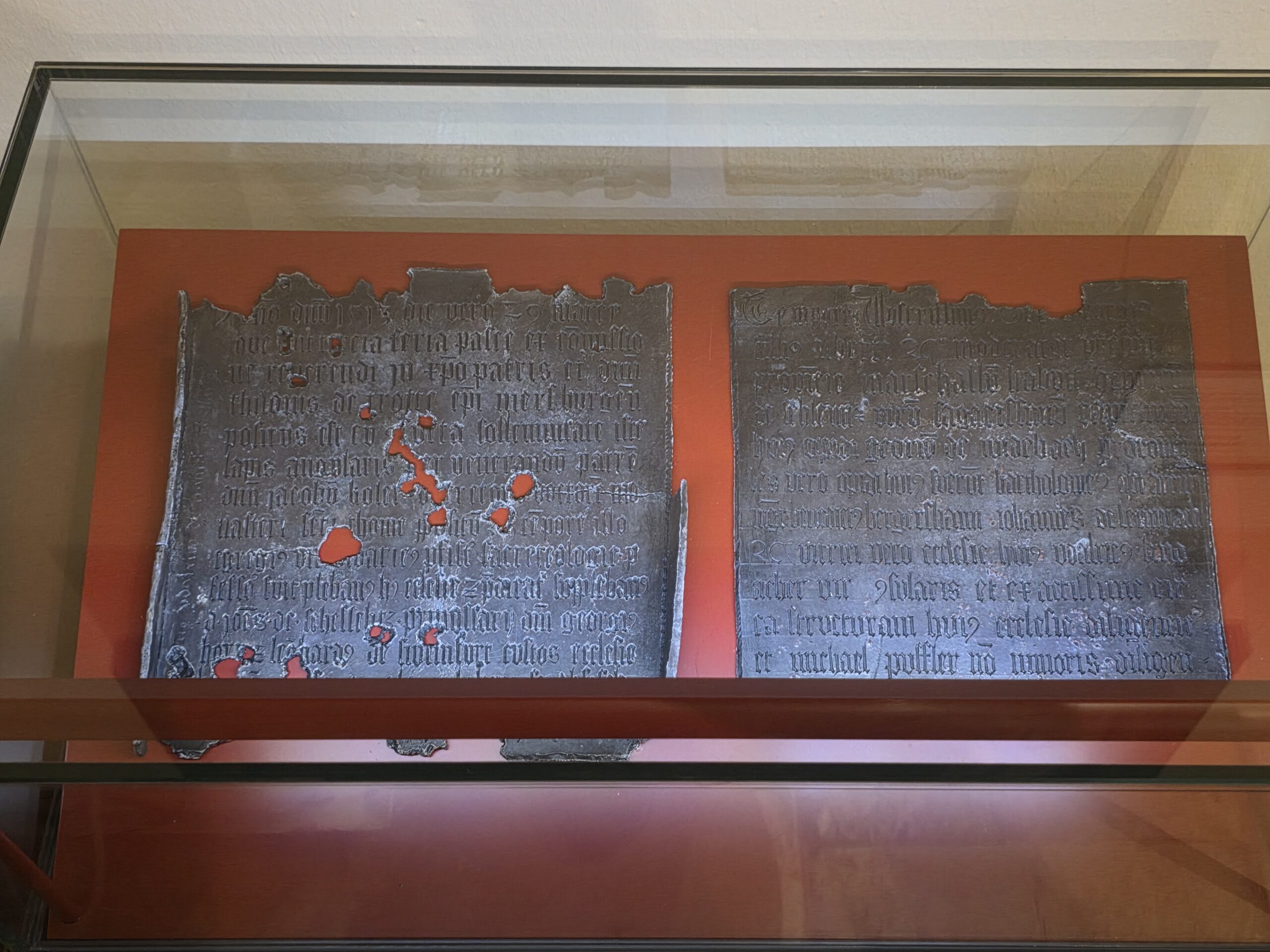

But, I like what’s left, clearly unrestored (unless it has been restored very badly) so it feels like it retains its authenticity. There’s a photo of the whole altarpiece at https://www.stadtmuseum.leipzig.de/DE-MUS-853418/objekt=PS000136 and I’ve learned that the base (so, the bit that’s actually still on display in the museum) is called a predella.

The museum also notes that the predella has half-length portraits of the holy virgins Dorothea, Catherine, Ursula and Margaret. These seem to be along the lines of the Capital Virgin Martyrs who are usually Dorothea, Catherine, Barbara and Margaret, but this line-up seems to change a bit depending on the whims of the medieval painter. Might as well mix it up with popping Ursula in though.

I digress though. Because the main altarpiece isn’t there, it does draw more attention to this section which is rather beautiful in its own right.