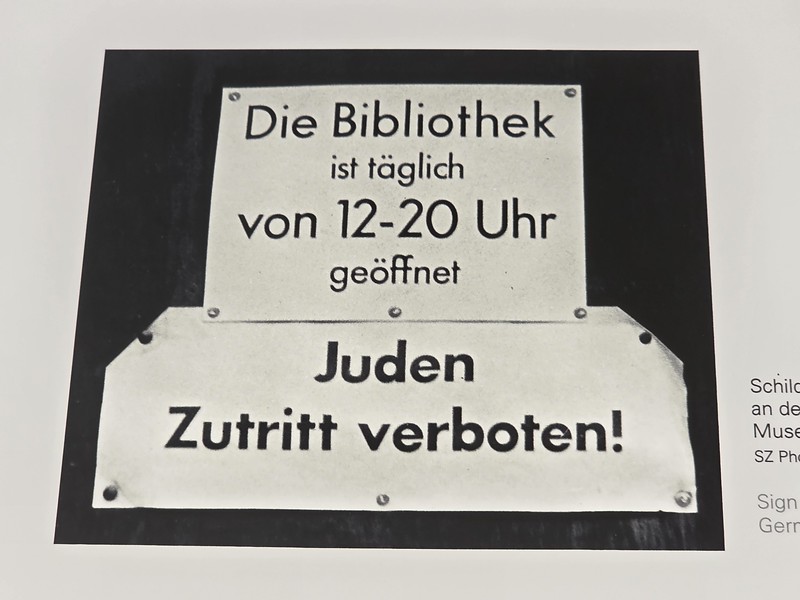

This is the former Führerbau, which is where the Munich Agreement was signed on 30 September 1938. This deal was agreed by Nazi Germany, Britain, France and Italy, handing the Sudetenland, which was Czechoslovakia’s fortified and industrial border region, to Hitler. Czechoslovakia weren’t at the table to discuss the matter and the British Neville Chamberlain and French Édouard Daladier accepted the transfer to avoid immediate conflict. Germany occupied the Sudetenland in October 1938, stripping Czechoslovakia of key defences and heavy industry and leaving it strategically crippled. Chamberlain also signed a brief Anglo-German declaration with Hitler expressing the wish for peaceful relations, hence the famous “peace for our time” line on his return to London.

The peace agreement didn’t hold, but Chamberlain perhaps didn’t really have much choice here. There was a chance in his mind that the peace agreement might work, but with hindsight it was inevitable that it would fail given Hitler’s evil intent. The document was signed in Hitler’s office, which is still there and used by the University of Music and Performing Arts Munich who now occupy the building. The building had been constructed between 1933 and 1937, part of the Königsplatz project that was part of Hitler’s architectural vision for the city.

The city authorities would have ideally liked to have demolished all of the Nazi era buildings, but they already had a shortage of usable structures post-war and there was nothing wrong with this one other than its association with evil. But, for me to see this building was sobering, it’s not that long ago that Chamberlain turned up here in the hope that he could avert a war. There’s no obvious connection with the past other than for this subtle sign which is in German, Czech and Slovak, a gesture towards the attack on their nations that was agreed here.

And the side of the building which was used by the US after the war as the central point to return artwork and cultural items stolen by Nazis back to their owners. It was given to the University of Music to give it a more positive use and to try and free it from its past. The more modern building to the right of the photo is the NS-Dokumentationszentrum, which during Hitler’s time was known as the Brown House.