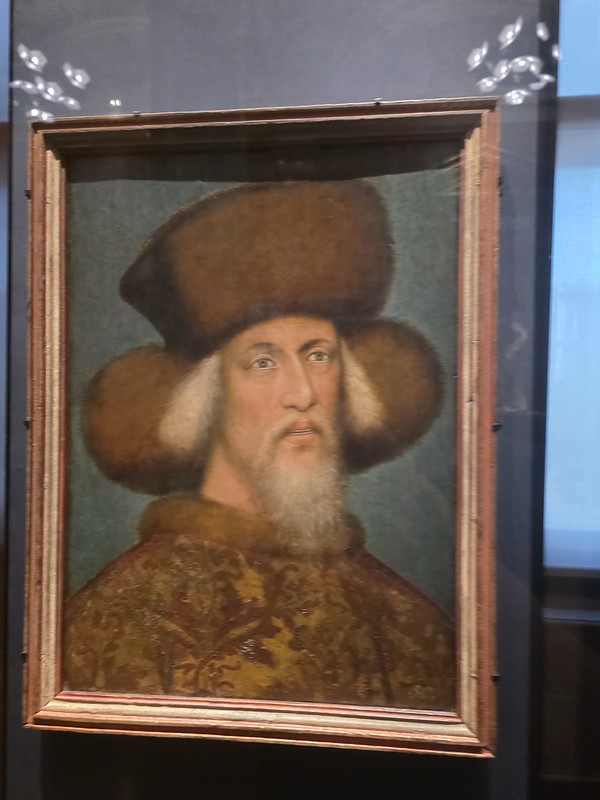

This formidable profile belongs to Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, as depicted in a late sixteenth-century copy after Bernhard Strigel. It now lives in the ever-rewarding Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, where the galleries are so stuffed with imperial grandeur that this little gem is easy to overlook. Although my two loyal blog readers will be surprised and delighted to discover that I took several hundred photos in this museum, so there will be plenty more of this riveting series about the artworks that they hold.

Strigel’s original work dates to the early 1500s, but this later copy, which was made by an unknown artist with a steady hand and a healthy respect for the Habsburg nose, carries on the visual tradition of showing Maximilian in all his stately glory. It’s got everything, the velvet backdrop, the finely detailed clothing, the meditative stare into the middle distance, and of course, that profile.

Now, it would be terribly unfair to criticise a man’s face 500 years after the fact, but even his contemporaries might have quietly agreed that Maximilian’s features were distinctive. But this portrait doesn’t try to soften anything and nor should it. It’s an honest portrayal of dynastic power and in an age before soft-focus filters and PR advisers, that sort of thing was all the rage. He’s not smiling, of course, Habsburgs rarely did, but he had a lot to think about, perhaps he’s just remembered the size of his empire and the fact that half of it was currently at war. There’s a charming little manor in the background, complete with gables and a decent bit of shrubbery. Whether this was symbolic of imperial reach or just the painter filling in the space with some pleasant countryside I have no idea, but I like the idea of him (and it was probably a male) doing the latter.

Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor from 1508 until his death in 1519, was born in 1459 the son of Frederick III and Eleanor of Portugal, and to be frank, he didn’t waste much time on hobbies when there were marriages to arrange and bits of Europe to hoover up. His marriage to Mary of Burgundy in 1477 gave him a claim to the vast Burgundian lands, and he spent a good part of his life either defending them, diplomatically squinting at maps, or enthusiastically marrying off his descendants to unsuspecting European royalty. The man essentially arguably invented Habsburg real estate strategy which was don’t fight too many wars, just marry aggressively and wait. While he never made it to Rome to be crowned by the Pope, largely because the Papal calendar was apparently a bit sub-optimal when it came to welcoming awkwardly ambitious emperors, he went ahead and started calling himself Elected Roman Emperor anyway. Fair play. Maximilian was a reformer in a rather haphazard way, dabbling in early postal systems, legal centralisation and he was a cultured guy.

Anyway, I have digressed a little, but this is certainly a memorable painting…..