Blog progress is a little slow at the moment given my laptop keeps malfunctioning, but hopefully my two loyal blog readers will persist until I can permanently fix the problem later this week. I arrived into Dortmund a few days ago expecting the usual German city break fodder, perhaps half-timbered houses, cobbled streets, medieval charm or even a large pretzel offered by someone in an apron. What I found instead was slightly less decadent, more smashed glass, graffiti and a friendly man who handed me a free ticket to the football museum (I liked him). Dortmund, it turns out, is not what I expected although my lack of research meant that I didn’t have a very defined vision anyway. And, I’m not even sure what it expects of itself, it’s a quirky place and it’s had some interesting decades historically.

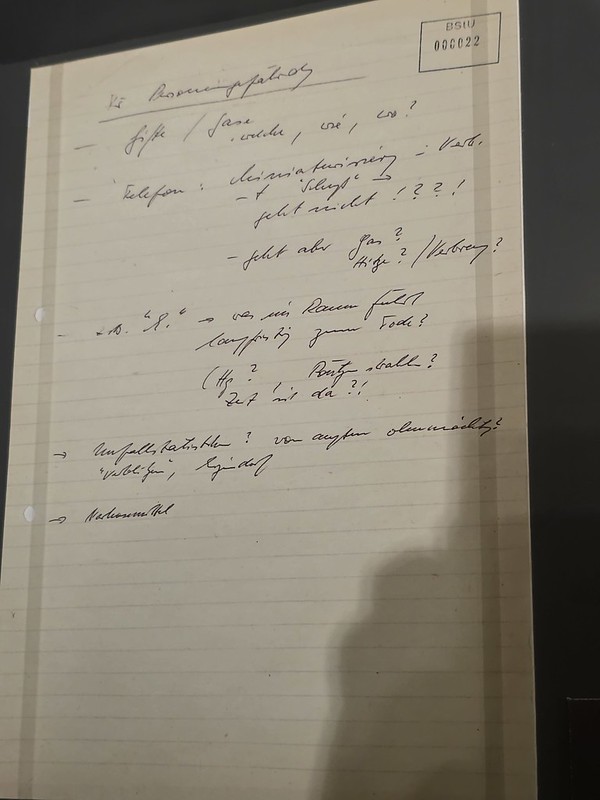

The city was pretty much flattened in the Second World War, quite literally, with over 90% of its centre destroyed in Allied bombing raids, and what stands today is, in many ways, an architectural shrug. After the war, there was even debate over whether to rebuild at all or simply start again elsewhere. A similar discussion was had with Warsaw, I do wonder whether turning a huge German city into a museum would have been something that might have been a permanent reminder of the Second World War, but I imagine the residents wanted normality to resume. Given that, the authorities opted for rebuilding, albeit in a way that perhaps prioritised function over flourish. The result is a city centre that follows the original medieval street lines but feels decidedly post-apocalyptic Ikea.

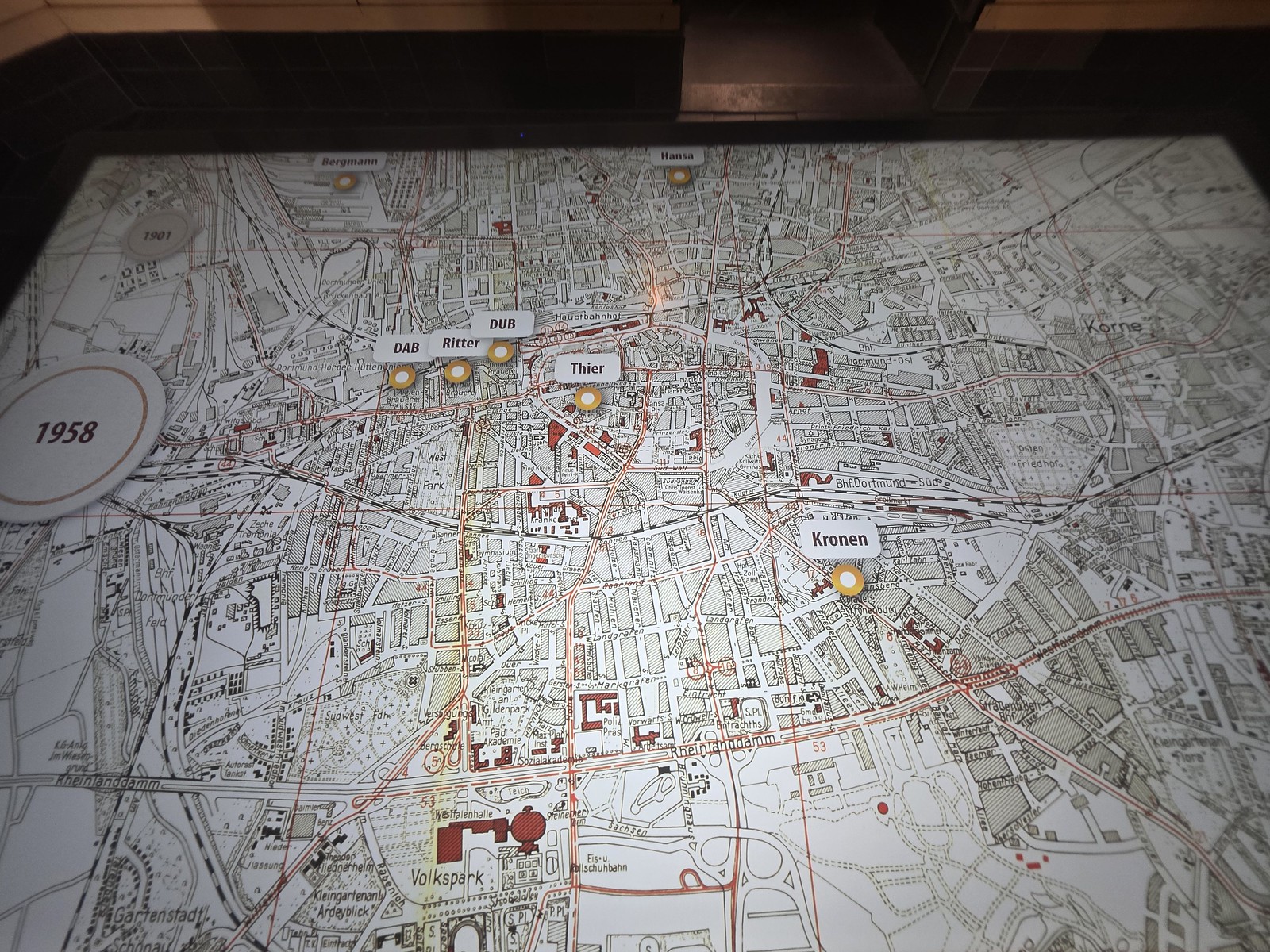

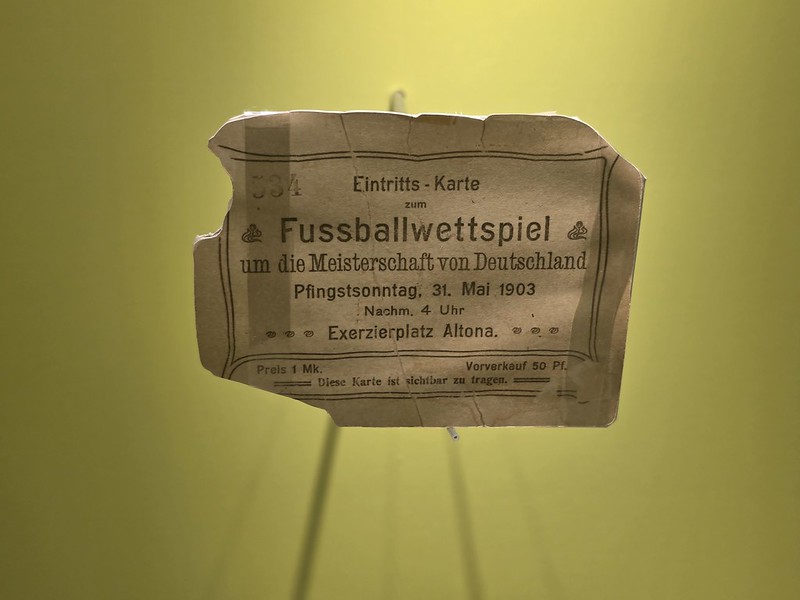

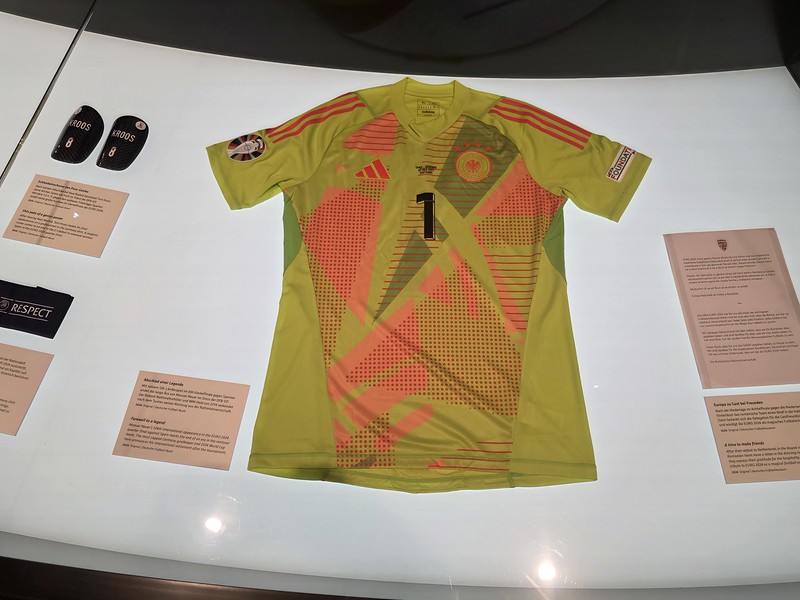

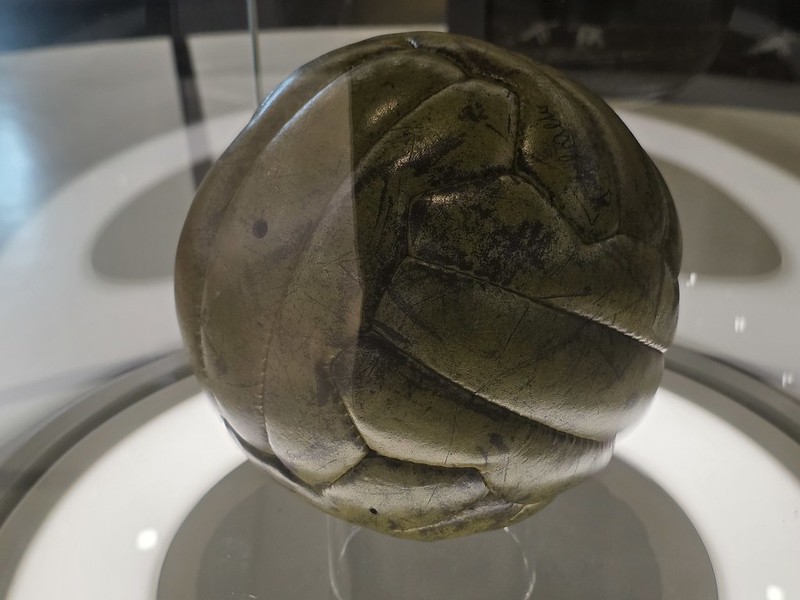

Heritage here is elusive. Some older buildings remain, especially as I edged further from the centre, but they don’t shout about it. In fact, most of them don’t say anything at all as there’s a distinct lack of signage about the city’s history, I’m unsure why they couldn’t have splashed out on a few more information boards. The only trail I encountered was football-related, although that was a common theme across the city in numerous ways and I can see why the German Football Museum was located here. In Dortmund, history is mostly told through football it seems, which is fitting, really, because the one thing this city has managed to preserve, polish and proudly display undamaged is its sporting spirit. The German Football Museum is an actual triumph as it’s glossy, modern and enthusiastic, so it’s not an entire surprise that so many other cities wanted to hold it. I wasn’t here when Borussia Dortmund were playing, but I imagine that there is an all consuming atmosphere and excited feel.

I walked a lot, as might be expected as it seemed the best way to understand the place, and to avoid the metro, which was pricey and I thought a little poorly signed. Walking revealed a functional city with reasonably well-maintained pavements, an interesting if slightly stern street layout and a distinct lack of benches. Want to sit? Buy a coffee or lean against a wall. Public space is clearly for movement, not musing. Green spaces, on the other hand, are plentiful when going further out and, in the summer heat I experienced (and hardly complained about once), heaving. Families sprawled across lawns, teenagers argued over Bluetooth speakers and a general sense of life pulsed through the parks. The former walled city ring provides a helpful visual guide for the pedestrian, a sort of phantom moat that lets you know where the city used to end and now endlessly continues into the suburbs.

I mentioned that the metro was pricey, and it cost me £3.50 to go three stops, but it was so hot that I found that a useful service and I wanted to experience the network. But that’s a ferocious price and it was no surprise to see just how many cars there were in the city. The signage on the metro was frankly not ideal and I sometimes wonder whether anyone from the network actually looks at the signage and follows it through, to see if it’s logical to visitors. Most networks don’t struggle with this. I note this as I ended up going back on myself and I don’t claim that I’m entirely competent in these matters, but a bit of assistance would have been useful from signs rather than having to seek comfort in Google Maps. I didn’t see a single staff member anywhere on the metro system which also felt sub-optimal in case anyone did need assistance.

I don’t like Deutsche Bahn for numerous reasons, but I don’t want to dwell on that for too long as balance is the key as my friend Richard always says. But there was again a lack of staff availability at the city’s main station, it was expensive and there was again poor signage (a bit of a theme in this city) although it was relatively clean and a staff member was enthusiastically clearing debris from the steps. I don’t like the ticket barriers on the UK rail network, but at least it means that staff are available and easy to find if anyone needs help. If I had a disability, I would have struggled here to get any assistance at the city’s main railway station. Having just come from Poland, the city was a country mile behind their neighbour in terms of public transport, whether that was price, ticket acquisition, cleanliness or signage. But, to give Dortmund some credit, their public transport network is integrated and extensive so it is very useable.

But Dortmund is not without its complications. The city’s scars are not just historical. There’s a visible and extensive homelessness problem, begging is common, anti-social behaviour is evident, there’s litter, graffiti and a smattering of smashed windows. One doorway with smashed windows was scrawled with the phrase “drug dealer”—not exactly the kind of street art you hope to discover on a cultural wander. And yet, despite these signs of wear and worry, I never felt unsafe, but the situation often felt sub-optimal, it was all just a bit gritty. The centre of the city has numerous shopping options with a number of international chains, although I didn’t notice any shopping malls, with independent shops located more in the suburbs. I’m not sure how many tourists the city gets, there isn’t much in the way of guided tours, city sightseeing buses or the like.

The people, however, were a different matter entirely. Everywhere I went, I encountered friendliness. A man with a spare football museum ticket gave it to me with a smile, although this arrangement rather confused the reception desk as two people arrived with joint tickets and one spoke fluent German and the other, well, didn’t. But back to the generality, the city’s bar staff were engaging and the staff in the hotels were particularly helpful. It was the kind of warmth that might catch one off guard when they’re surrounded by concrete and broken glass. Dortmund’s people are, if anything, its redemption arc. It’s a multi-cultural city with a fair amount of immigration, which brings a breadth of food and cultural depth along with it. The city has depopulated over the last few decades and I wonder whether the migrant population has been used to prop up the local economy, but either way, there’s a substantial Turkish community here and from what I could see they have integrated well.

On Friday evening, the city centre came to life following a day where a fair amount of stuff seemed shut. A food and drink event had taken over the heart of town, and for a few hours, it all made sense in terms of its vibrancy. This is what Dortmund is striving for: community, togetherness, a reason to gather. It was joyous, and it felt like the city had shrugged off its trauma just long enough to have a dance and a sausage. I’m sure locals would tell me that the sense of community in the city is just fine, but in the couple of days I was there, it wasn’t blatantly obvious to me. Beer, maybe oddly but maybe not as it’s Germany, is where Dortmund seems oddly restrained. The local Pils dominate the arrangements, with little craft variety, but this is a constant theme that I go on about. The bars are more old-school than cutting-edge, but again, the service was warm and the beer was refreshing. You won’t find pretentious (also read delicious) flights of IPA here, just solid lager and people who’ll chat to you about football, the weather and how much better things used to be. One day the craft beer will come though, I’m confident about that, the Reinheitsgebot will just have to evolve. I did go to the brewery museum, a recommended affair that is free of charge and relatively extensive.

Perhaps the biggest surprise was the persistence of cash. Many places didn’t accept cards, and finding a cash machine was more of a treasure hunt than a convenience. For a city with such modern trappings, Dortmund clings to coins and notes with curious enthusiasm. The whole arrangement is a nuisance, it’s evident from the signs, often in English, that tourists expect cards to be an option and the direction of travel here seems to be one way in terms of giving visitors choice. Numerous takeaway stands made clear they accepted cards, fearful likely of losing considerable amounts of trade if they didn’t.

If I had to sum Dortmund up in one word, it would be: troubled. But that feels too harsh, although there’s no immediate beauty to be found here as there might be in other German cities. Perhaps “full of potential” is better. This is a former industrial city which has had to change into a service led economy, research and tech is pretty big here, but that’s a challenging transformation. It’s a city with bruises but also heart. It’s not polished or pristine, but it’s trying its best. And perhaps it’s worth visiting not because it’s perfect, but because it isn’t. I think my return visit to Dortmund, as I’m sure that there will be one, will be made with an open mind, a pair of sturdy shoes and some spare change. I might not fall in love (it’s not Poland or the Baltic states after all), but I might, just for a moment, understand it a bit better and it’s certainly a resilient place. Oh, and it loves football.