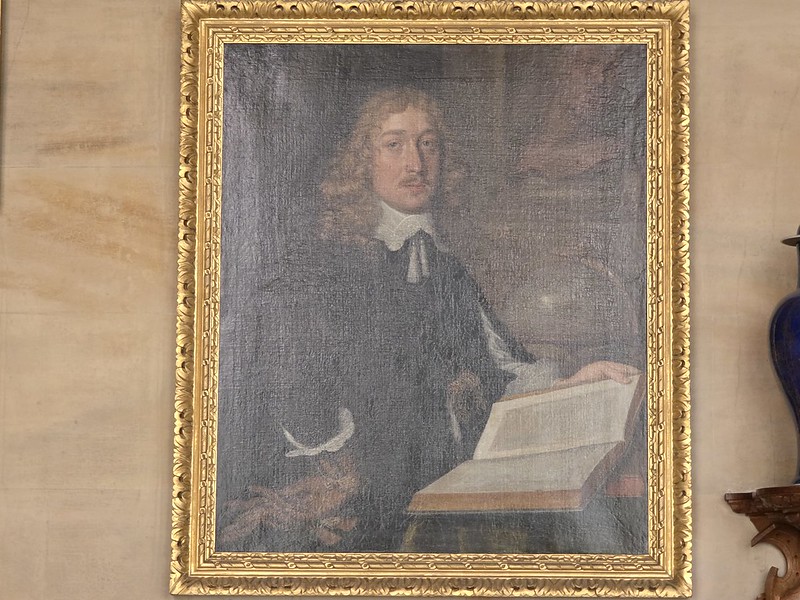

This painting is located in the billiards room of Charlecote House and it’s of George Lucy (1714-1786) who was also known as the Bachelor Squire. The painting is by Pompeo Girolamo Batoni (1708 – 1787) and it’s that which I’m most interested in here as George had a long and complex life that is far beyond any short blog post. Batoni became famous for painting members of the British aristocracy, and indeed many others, who were visiting Italy as part of the Grand Tour. George Lucy himself noted:

“I have shown my face and person to the celebrated Pompeo Battoni, to take the likeness thereof. These painters are great men, and must be flattered for ‘tis the custom here, not to think themselves obliged to you for employing them, but that they oblige you by being employed.”

George Lucy arrived in Naples in 1756 and soon realised that he didn’t quite look the part and he promptly asked for his clothes to be shipped from Charlecote to Italy. I’m not sure how you would go about doing that, as UPS weren’t quite fully formed at that point, but it didn’t do much good as the vessel they were on was promptly intercepted by Moorish pirates and his fineries ended up in Algiers. It was in 1758 that he moved onto Rome, with what I assume was a new wardrobe he had acquired out there, as he was clearly in no rush on this Grand Tour, and it was then that he commissioned Batoni to paint him. This was a considerable honour, the artist didn’t speed paint and he was careful what work he took on.

Lucy paid 40 guineas for this artwork which was completed after he had left Rome and so it was shipped back, fortunately not being intercepted by pirates on this occasion. He looks very on-trend in the painting, he’s wearing fancy and fine clothes, he looks elegant and he looks very travelled. Batoni was often said to have inspired Thomas Gainsborough and on Lucy’s return he also had a painting commissioned by the British artist. The phrase Bachelor Squire was polite, he was known by others as the “wild bachelor”, obsessed with travel, society and food. I make no comment. Lucy found the process a bit of a faff, he had to sit on three occasions for Batoni and he wrote to his housekeeper at Charlecote that “he would not undertake to do me in less time”.

Batoni’s paintings are scattered everywhere today, but this one of George Lucy hasn’t gone anywhere far since it was installed in Charlecote in the late 1750s. Along with the entire house, it was given to the National Trust in 1946.