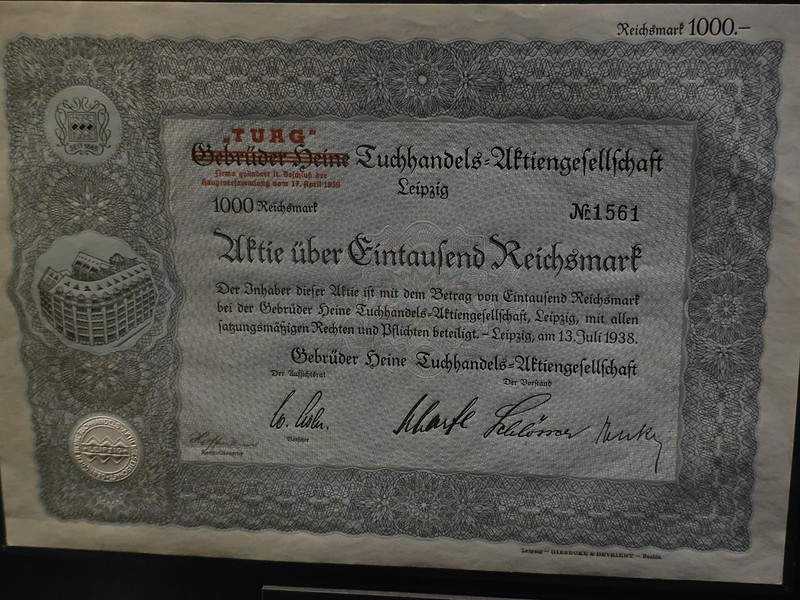

This share certificate in the museum is from Leipzig, dated 13 July 1938, and looks like a neatly printed piece of paper declaring ownership of 1,000 Reichsmark in the Gebrüder Heine Tuchhandels-Aktiengesellschaft, a textile trading company. But as with so many relics from the late 1930s, this is much more sinister. It’s the story of a business which was forcibly taken from its Jewish owners, absorbed into the machinery of the Nazi economy, and stripped of its name, its history and its identity.

Gebrüder Heine had been a respected textile firm in Leipzig, a city that before 1933 was one of Europe’s great trading hubs. Jewish businesses like Heine’s were central to Leipzig’s commercial life, especially in textiles and fur. But by the late 1930s, the Nazis had made it increasingly impossible for Jewish entrepreneurs to survive. Laws, boycotts and systematic harassment had already driven many to ruin. For those still operating, the so-called “Aryanisation” policies brought the final blow which were forced sales at a fraction of true value, under threat and coercion.

In July 1938, Gebrüder Heine’s owners were compelled to sell and it was likely at a hugely underflated price. The buyer was TUAG (Tuchhandels-Union AG), a non-Jewish firm which took over the assets, premises and business operations. The company was rebranded under new management, its Jewish founders expelled from both their livelihood and their rights as shareholders.

This share certificate, issued in the final days of the firm’s existence, reflects that transition. It proclaims ownership in Gebrüder Heine Tuchhandels-AG, but the red overprint at the top marks the shift of power. The paper itself is meticulously designed, printed by Giesecke & Devrient, and stamped with seals and signatures that convey legitimacy and stability.

This must have been a bitter moment for the former owners, forced effectively to sell their business by the state. There was still a bureaucratic process, but it offered Jewish businesses nearly no protection or rights.

However, this story does have a rather more positive ending as Walter Heine was able to escape to Australia where he joined the military and promptly started what became a global commodity company called Heine Brothers after the end of the war. Here’s an interesting article about the family’s fortunes after they were forced out of Germany.