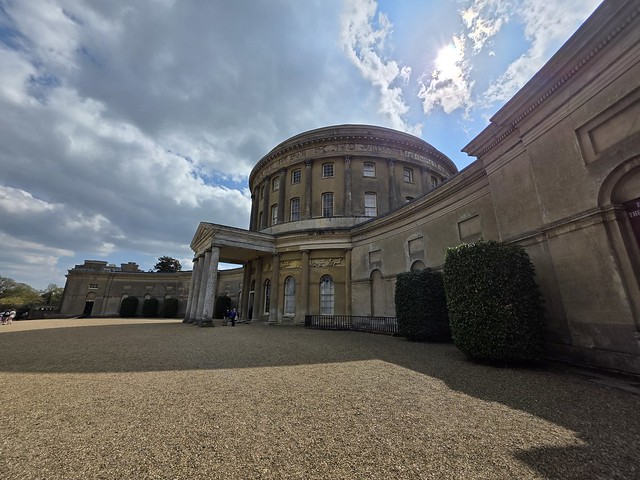

Liam and I popped into Ickworth House on the way back to Norwich and I realised that I hadn’t visited here for 40 years. I don’t wish to linger on this thought as it doesn’t fit the obvious truism (obvious to me) that I’m a millennial.

The parkland in front of the property.

The rather nice second hand bookshop, but I restrained myself from buying anything.

Liam playing bagatelle, which is likely a forerunner of bar billiards. On that point, I haven’t yet mentioned in detail my day at the World Championships, I’ll get to that soon hopefully… Although there’s a lot of stuff on this blog I’m meant to be getting around to.

I loved that they’ve put books into lots of niches around the house. If I had a large property, which is unlikely and a bit unnecessary, I’d likely do something similar and the situation would soon get out of control. Liam commented something similar, but I ignored him.

Anyway, to set the timeline here:

1779: Frederick Hervey (later the ‘Earl-Bishop’) inherits the Ickworth estate.

c. 1795: The Earl-Bishop commissions initial Neoclassical designs for a new house from Italian architect Mario Asprucci the Younger. The concept is primarily for an art gallery.

1795 / 1796: Construction begins. Irish architects Francis and Joseph Sandys adapt Asprucci’s designs and oversee the work.

1798: The Earl-Bishop’s extensive art collection, intended for Ickworth, is confiscated in Rome by Napoleonic forces.

1803: The Earl-Bishop dies in Italy. Construction halts, leaving the house, primarily the Rotunda, as an unfinished shell.

c. 1821 – 1830: Construction resumes under the Earl-Bishop’s son, Frederick William Hervey (later 1st Marquess of Bristol). The main structure, including the wings, is completed. Architect John Field is involved in adapting and completing the interiors.

1829: The 1st Marquess and his family move into the completed house. The East Wing becomes the family residence, and the Rotunda is used for display and entertaining. The West Wing remains largely unfinished.

c. 1830: Interior fittings, including marble fireplaces, Scagliola columns, and coved ceilings, are largely complete.

c. 1879: The 3rd Marquess commissions architect Francis Penrose for internal improvements. The Pompeian Room (decorated by J.D. Crace) and the Smoking Room are created in projecting bays off the linking corridors.

c. 1907 – 1910: The 4th Marquess commissions architect Sir Reginald Blomfield (or possibly A.C. Blomfield) for further interior alterations, including remodelling the main staircase in the Rotunda and modernisations in the East Wing.

1930s: Theodora, Marchioness of Bristol, renovates the servants’ quarters in the Rotunda basement, adding modern amenities like electricity and improved plumbing.

1956: Following the death of the 4th Marquess, the house, contents, park, and endowment are transferred to the National Trust via HM Treasury in lieu of death duties. The Hervey family retains a lease on the East Wing.

1998: The 7th Marquess sells the remaining term of the lease on the East Wing to the National Trust, ending the family’s residential connection.

2002: The East Wing is converted and opens as The Ickworth Hotel, operated under lease from the National Trust. Childs Sulzmann Architects are involved.

2006: The previously unfinished West Wing is completed and opened as a visitor centre, restaurant, shop, and events venue, in partnership with Sodexo Prestige. Hopkins Architects are associated with this phase.

2018 – 2020: The major ‘Ickworth Uncovered’ conservation project takes place, involving the complete re-roofing of the Rotunda dome and East Link corridor.

As is my wont, I’ll post numerous other things separately about the property, but I was genuinely very impressed with the volunteers here who were pro-active, engaging and keen to tell visitors about the history of the building. As I like wittering on about history, this did extend our visit somewhat, but it’s always a delight when there’s an enthusiasm from everyone involved with the project. The navigation route around the house was also carefully laid out and it was clear where to go, there has been a lot of thought put into this entire operation.