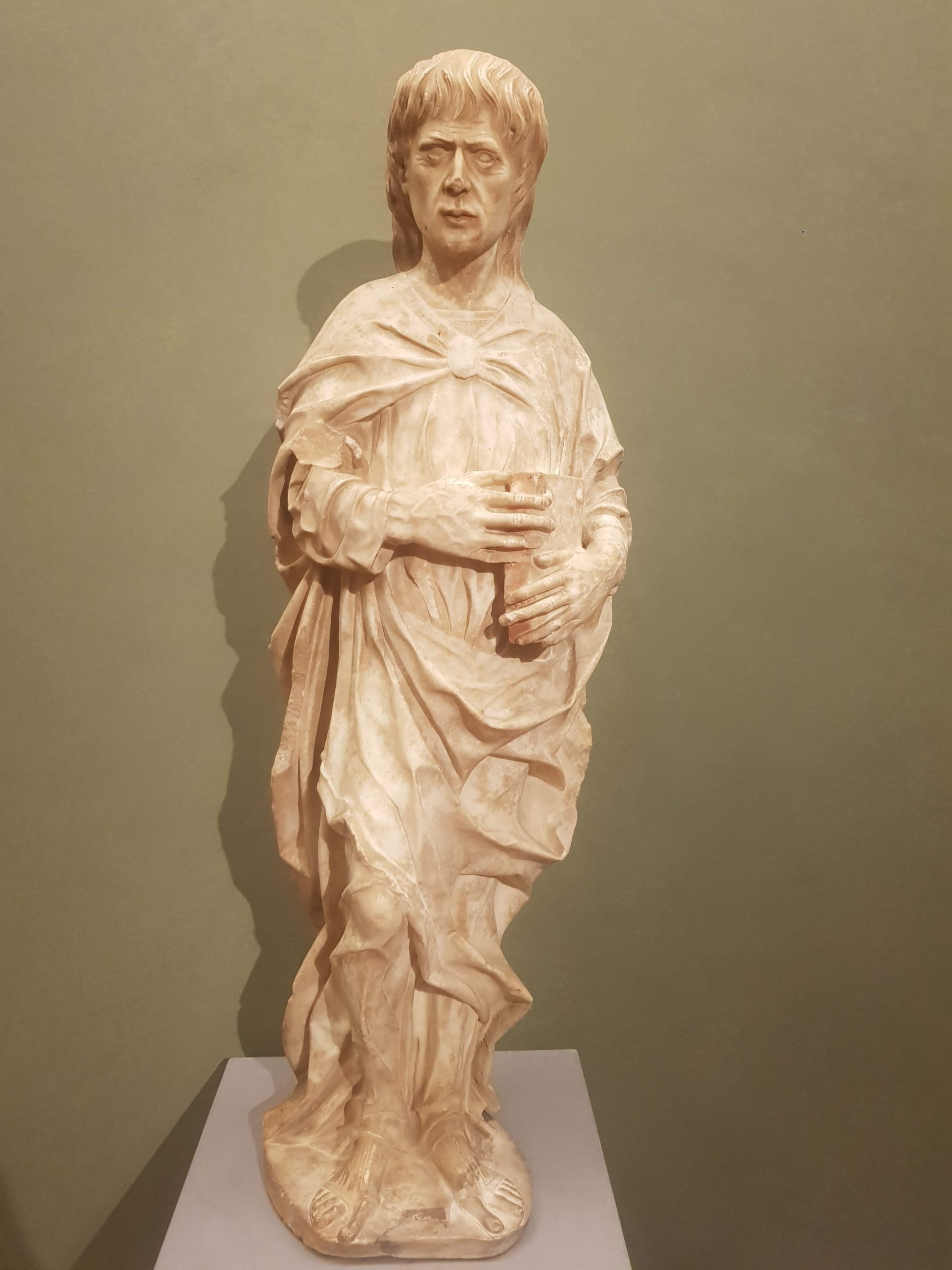

This statue was once located on the north side of Florence Cathedral and depicts King David. It was sculpted by Andrea Pisano (1290-1348), who became the Master of Works at the Cathedral in 1340, between 1337 and 1341. This sculpture was part of a set of depictions that were designed to show those prophesied the coming of Jesus.

Category: Florence

-

Florence – Uffizi Gallery (1470s Sculpture of an Evangelist)

Another part of the legacy provided to the Uffizi by the controversial Count Alessandro Contini-Bonacossi, there’s not a vast amount known about this marble sculpture. However, experts have managed to pinpoint it to likely being from between 1475 and 1480 because of the style, they suspect it’s of St. John and it’s likely from the circle of artists linked to Giovanni Antonio Amadeo. Certainly an impressive piece of deduction by the curators to ascertain all of that. And, other than a dent to the nose, it’s in a pretty good state of repair given it’s over 500 years old.

-

Florence – Uffizi Gallery (The Supper at Emmaus by Vincenzo Cateno)

Painted at some point between 1515 and 1520 by Vincenzo Cateno, the artwork shows the two apostles meeting with Christ after He has risen. The information by the painting notes that the figure in black was likely the patron who funded the artwork.

The information also notes that “the two apostles recognise their Master when Christ blesses and breaks the bread just as He had done at the Last Supper”. The artist was Venetian and lived between 1480 until around 1531, with this painting being part of the legacy provided by Count Alessandro Contini-Bonacossi (who appears to have been an enormously controversial figure) who died in Florence in 1955.

-

Florence – Museo Galileo (Organum Mathematicum)

This is an Italian Organum Mathematicum from the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century. I didn’t have a clue what this meant, but again, the museum’s web-site has the answer, it’s effectively a portable encyclopaedia.

The museum describes more elegantly than I could:

“The inside of the chest is divided into nine compartments, one for each of the following subjects: Arithmetic, Geometry, Art of fortifications, Chronology, Horography, Astronomy, Astrology, Steganography, and Music. Each compartment contains twenty-four small rods ending in a coloured triangular tip. On each of the nine series of twenty-four small rods are inscribed definitions and information on the corresponding subject. At least one rod in each of the nine compartments has a black tip and constitutes the application table, which gives the rule for proper use. To multiply 74 x 8, for example, one removes the black-tipped rod from the Arithmetic compartment and places it next to the rods carrying the numbers 7 and 4 at the top. The eighth line on the black-tipped rod gives the desired product.”

I think it’s delightful, Wikipedia notes just how important they were:

“Kircher adopted some of the ideas in the Organum from preexisting inventions like Napier’s bones, almanacs, and his own Arca Musarithmica. Like other calculating devices of the period, the Organum prefigures modern computing technology. Yet, due to its general lack of adoption, it remains an interesting but obscure footnote in the history of information technology.”

Nathan and Richard would definitely one.

-

Florence – Museo Galileo (Box for Mathematical Instruments)

This is one of those excellent museums which gives some brief information about the object on a panel nearby, whilst adding more details on-line for those who want to find out more. So, the description by the object simply said that this was an eighteenth-century box for storing mathematical instruments. On-line, there’s lots more information about what’s inside the box:

“The inside contains a drawer and three shelves carrying the instruments, some of which are missing. There are now several proportional compasses, reduction compasses and dividers; polymetric compasses (i.e., capable of multiple measurements); a plumb level; a few squares including a double square; a radio latino; several rulers; a quadrant; a surveying compass; a trigonometer, and a cylindrical weight tapering to a point and fitted with a ring.”

I don’t really have that many mathematical instruments to store, but if I did, I’d like it in a grand red book-like box like this. Incidentally, I had to look up what a radio latino was, apparently it’s “a measuring instrument used in surveying and military engineering starting in the 16th century”.

-

Florence – Museo Galileo (Polyhedral Dial)

Thank goodness for signage, as I didn’t have a clue what this was, but apparently, it’s a polyhedral dial from the seventeenth century. It’s a sundial, which allows the user to see the time in a number of different ways. Initially I thought that it was wooden, but it’s made from stone and the figures are painted on. Only one of the gnomons remains (it’s on the rear side, so not visible in the photo), which are the little things which stick out to cast the shadow (I’m not sure that’s the most technical explanation).

The museum have a better photo at https://catalogue.museogalileo.it/gallery/PolyhedralDialInv2495.html.

-

Florence – Uffizi Gallery (Parade Hat)

This parade hat dates from the second half of the fifteenth century, which makes it a fascinating exhibit for any museum. Of course, this being the Uffizi, their collections are exemplary and not only has this item been preserved, but it’s thought that it might have belonged to Pope Pius II or Pope Pius III (he’s the Pope who was in the position for just 26 days). It’s made from velvet, with silk and gold braid, so a very elegant piece.

-

Florence – Uffizi Gallery (Hercules Slaying the Centaur Nessus)

I thought at first that this sculpture was Roman, but only the torso of the centaur (half man, half horse) remained and so the rest, including the head and legs of the centaur and the entirety of Hercules, was added in the sixteenth century. Well, other than the feet of Hercules, they’re mostly original Roman as well. It depicts Hercules slaying Nessus who had tried to kill Deianira, the wife of Hercules.

The element that I liked most about this sculpture is that it has been on display in this corridor since 1595 and it’s near the main entrance to the upper floors of the gallery, which is where visitors start their tour. There must have been countless millions who have looked at this sculpture and there can’t be many artworks in the world that have had this uninterrupted period of being on public display.

The sixteenth century additions to the sculpture were made by Giovanni Caccini, but over the last few years there has been a restoration of it and they’ve been able to see exactly where the joins in the sculpture have been made, the merging of the old and new. They also discovered that the stance of the centaur was changed slightly and that more work was done on the foot of Hercules than had previously been realised. The same recent re-examination of the sculpture also found that the original marble is from Asia, whereas Caccini used marble from Tuscany.

-

Florence – Uffizi Gallery (I Corridoi di Galleria)

The corridors of the Uffizi are iconic and they form the base of the gallery’s large collections, with rooms leading off them. And what is interesting is that the word ‘gallery’ in the sense of displaying artworks or artefacts may derive from here, when the word originally meant an area at the side of a building.

This is the view towards the Palazzo Vecchio from the crossing gallery, with the top floor windows on each side containing the corridors.

The frescoes on the ceiling date to the late sixteenth century and the early seventeenth centuries. There would have been tapestries on the walls, but these have now been removed as the light was damaging them. As an introduction to the museum, these corridors are an exciting sight as they stretch off into the distance.

-

Florence – Column of Justice

This 11 metre high column (or in Italian, the Colonna della Giustizia) is located at Piazza Santa Trinita and it has a much longer history than I realised at the time. It’s a Roman column that was at the Baths of Caracalla in Rome, but which was given by Pope Pius IV to Cosimo I de’ Medici. This gift perhaps makes more sense when taking into account the Pope’s name before he took on the role, which was Giovanni Angelo Medici.

The move from Rome to Florence sounds a bloody nuisance, they could only move it a few hundred metres a day and it took well over a year to get the column to the city. I wonder whether a more practical present could have been offered than a 50-ton column, perhaps a flock of sheep or something. Or maybe just a book. When the column finally arrived in Florence in 1563, they were able to get it standing on the pedestal in just a few hours, although then they had to work out what they were going to put on top.

For just over a decade there was a wooden statue plonked on the top, although to be fair, it’s so high they could have got away with nearly anything. In 1580, a statue of Justice designed by Ammannati was installed, comprised of three fragments of Roman sculptures. Shortly after the statue was installed some boys were accused of stealing from a jewellers nearby and were banned from the Ponte Vecchio where the shop was located. The boys denied the theft, although they weren’t believed, but the thefts continued. A long time after, the stones were discovered on the scales of the statue on the top of the column, they had been stolen by magpies who liked the bright colours.

It’s an impressive column, but it’s perhaps a shame that they can’t reduce the traffic which goes by it. Although not on a main road, there were numerous vehicles driving down and the column deserves some more peaceful surroundings.