The Baltic Way, also known as the Baltic Chain, was a pivotal moment in the history of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. On 23 August 23 1989, approximately two million people joined hands to form a human chain stretching 675 kilometres (419 miles) across the three Baltic states. This peaceful political demonstration marked the 50th anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, a secret agreement between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that led to the occupation and annexation of the Baltic states. It’s worth remembering that the Soviets lied about this for decades, desperate to hide the truth from the people.

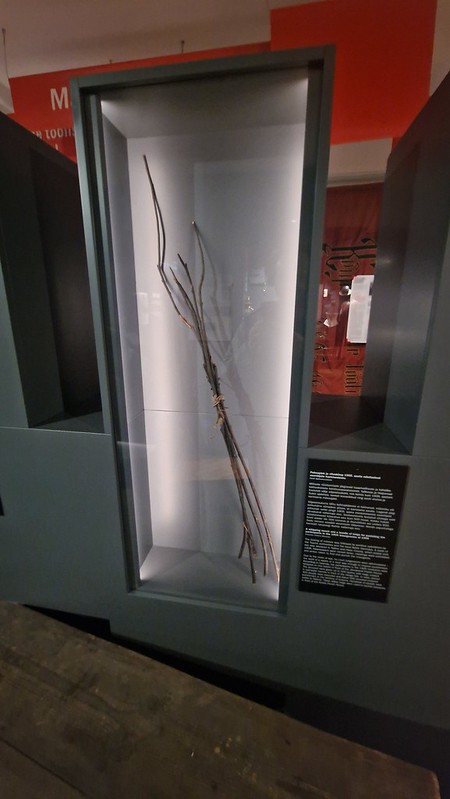

The Baltic Way was a culmination of angry people who were fed up with the disaster that was the USSR and they wanted freedom for their nations. The demonstration was organised by the national movements of the three countries, Rahvarinne in Estonia, Tautas fronte in Latvia, and Sąjūdis in Lithuania. On 23 August 1989, two million people held hands in a remarkable show of solidarity. The chain stretched from Tallinn, the capital of Estonia, through Riga, the capital of Latvia, to Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania. The event was accompanied by the singing of national anthems and the ringing of church bells, with this badge being worn by one of the members of the crowd, although the museum doesn’t mention who the owner was.

What did the Soviet Government do about the Baltic Way? Absolutely nothing other than panic a bit. Two of the most evil men in twentieth century politics, Nicolae Ceaușescu and Erich Honecker, actually offered troops to force the break-up of the human chain. Honecker was fortunate not to suffer the fate of Ceaușescu, both guilty of crimes against humanity. The event is commemorated annually in the Baltic states and is a reminder of how freedom was taken away from the people. The house of cards is always near to toppling over in dictatorships.